Understanding the Informed Consent Process for Dentists

From a medicolegal perspective and on ethical and moral grounds, obtaining informed consent from patients before treatment is critical. In fact, in many if not all malpractice suits, one of the primary elements of the complaint indicates a lack of informed consent before treatment. Basically, plaintiffs claim that they did not fully understand the risks of undergoing a given treatment and alternative options, including the option to do nothing (and risks of doing nothing).

While most clinicians would likely argue that their patients are well-educated, a recent study in JADA1 suggests that even with signed written informed consent forms, patients may not understand what dentists think they do.

The 7 elements of informed consent

Seven elements of informed consent have been identified,2 and informed consent is typically not considered to be adequately obtained unless all of these have been met by the patient or their legal guardian/representative:

- The patient must be competent to understand what is presented.

- The patient must voluntarily make the decision, not under any kind of coercion.

- Material information that’s essential to making an informed decision must be fully shared.

- The plan for treatment must be clear.

- The patient must adequately comprehend material information and the plan.

- The patient must clearly make a decision to proceed with the plan.

- The treatment plan must be authorized by the patient.

Informed refusal occurs only when Elements #1–5 have been met but the patient opts not to accept the plan.

While it’s tempting for dentists to assume that they’re obtaining informed consent when patients read and sign a form to acknowledge understanding, signed forms only memorialize an attempt to inform the patient. Forms do not replace active discussion. Considering that the “average” American reads at a seventh- or eighth-grade level,3 it’s doubtful most patients understand fully the terminology used in informed consent documents like paresthesia, loss of function, discomfort, etc. Therefore, obtaining informed consent and refusal is a process, not a single event.

The process of informed consent

The informed consent process must be a cultural norm in dental practice, and the “Tell, Show, Do” technique must be used as much as possible. For example, the process begins with a handshake with a new patient in my practice. During every conversation regarding the patient’s dental health, I aim to educate them about some aspect of their condition, even if it’s just, “You’re doing great! Your gums aren’t bleeding at all, but there are some issues with your teeth I’d like to explore with you.”

While the person who can actually obtain informed consent depends on the laws of each state, a good rule of thumb is that whoever is actually performing a given procedure should be the person to obtain the informed consent. However, all staff members can and should play a significant role.

- Assistants, for example, can educate patients, introduce appropriate brochures, show patients videos, review informed consent forms with patients, and witness any discussion that doctors have with their patients.

- Fees can be addressed by any staff member who typically handles that responsibility in the practice.

- The doctor’s role in obtaining informed consent can be as simple as making it a point to ask the patient if they have any questions or concerns about the treatment being provided and to verify with the patient what’s planned for the appointment before initiating any treatment.

In my office, for example, it’s routine for me to sit down just before donning my gloves or mask, while my hands are drying from washing or disinfection, and say something like, “Good morning, Mrs. Jones. I understand we will be repairing some of your front teeth today, and I know that Ashley has discussed this with you. Is that right? Do you have any questions or concerns before we begin?” By doing so, if my team members have handled all the other details, I am solidifying the informed consent process for that day.

A friend of mine, Dr. William Leffler, JD, simplified the elements in the informed consent process.4 He suggests asking yourself before starting any treatment: “Is (your patient) in the BARN?” The acronym BARN means:

- B: Do they understand the BENEFITS of your proposed treatment?

- A: Do they know their reasonable ALTERNATIVES to your proposed treatment?

- R: Do they understand the reasonably foreseen RISKS of your proposed treatment?

- N: Do they know what will happen if they do NOTHING?

Some studies have been done in medical and dental literature about the effectiveness of the informed consent process.1

- Essentially, verbal discussions between a provider and a patient are insufficient.

- Signed forms are problematic without discussion, due to literacy issues and the necessary understanding of detail.

- When a provider has a verbal discussion and provides informed consent forms, understanding is improved, but still tends to fall short of optimal informed consent/refusal.

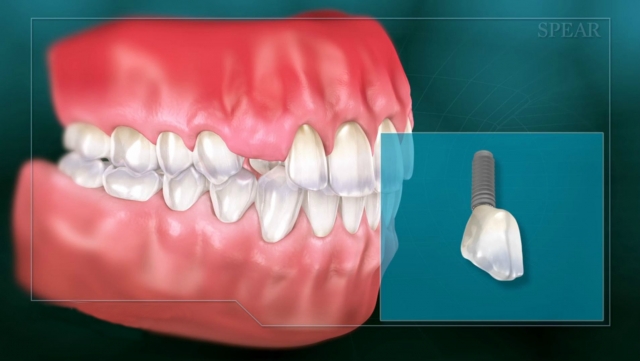

- However, recall by patients and understanding of the risks, benefits, and alternatives to treatments are significantly improved by adding adjunctive materials like brochures, especially with animations or videos related to planned procedures.

This parallels what effective educators understand about how people learn: Some learn by seeing, others by doing, and some by reading; all learn by engaging.

Ways to engage your dental patients

Dentistry offers many opportunities to engage our patients. Many companies for implants, branded crown materials, etc., produce brochures and pamphlets; however, when we use these materials, we must be careful to ensure they objectively discuss other reasonable options. Website use has increased exponentially over the past decade, primarily for marketing purposes, and many practices discuss the services they provide on their websites. A bit of caution here: Be sure the information is objective and honest if you want to use it as part of the informed consent process. Videos are also available to show patients about planned procedures.

I’ve had the good fortune to use several types of videos for patient education over the years in my practice, and even served as an author for one particular company. I believe Spear’s patient education videos and materials are by far the best I have seen: They allow the dentist to print out written summaries of the information presented in the well-made, narrated animations, and the videos are even available to embed into individual practice websites. For an example of how this can be done, look at my practice website.

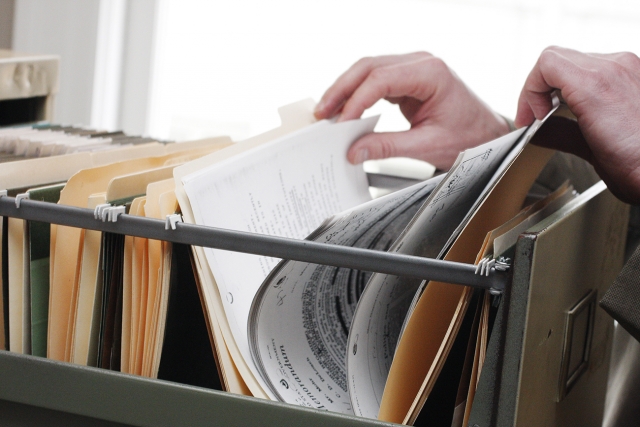

The importance of keeping a record

Incidentally, from a risk management perspective, it’s wise to keep a hard or scanned copy of any literature you have freely available to your patients (with dates that the materials came into use and ceased to be in use in your practice), even if they’re simply available in a conspicuously displayed rack in your private office or reception lounge. For digital media, be sure to record the source (website) of the producing company, or keep saved copies of videos when possible. One company I know does not allow copying of its proprietary videos, and it updates them yearly; make sure you note this. Even if you have your own website that’s been rewritten, or a company is out of business and has digital media that you used, the pages can usually be retrieved through sites like WayBackMachine.

In the event of a lawsuit or board investigation, it may be extremely helpful to be able to prove that you had multiple sources of freely available information to assist in the informed consent process and to establish that patient education is the culture of your practice. However, be sure to carefully read any brochures or promotional literature you have in your office before making it available to your patients! Plaintiff attorneys may demand copies of all marketing and educational materials that could have been available to their clients in an effort to prove that you made no attempt to provide alternative sources of information to make procedures more understandable.

The fact of the matter is, our patients likely are not as informed as we think they are. Written informed consent, discussion between the dentist and the patient about treatment at the patient’s level of understanding, and the use of appropriate animations and visual aids together provide for effective informed consent. As the authors of the JADA article conclude:

“According to the available literature, adult dental patients do not always show adequate levels of understanding and information recollection from their informed consent processes, although they usually think they understood the information provided well. Usually, an immediate improvement of understanding and recall capabilities among adult dental patients was gained when adjunct information methods were used.”1

References

- Moreira, N. C. F., Pacheco-Pereira, C., Keenan, L., Cummings, G., & Flores-Mir, C. (2016). Informed consent comprehension and recollection in adult dental patients: A systematic review. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 147(8), 605-619.

- http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/informed+consent

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Literacy_in_the_United_States

- http://www.dentaleconomics.com/articles/print/volume-102/issue-6/feature/are-your-patients-in-the-barn-or-are-you-in-the-doghouse.html

SPEAR ONLINE

Team Training to Empower Every Role

Spear Online encourages team alignment with role-specific CE video lessons and other resources that enable office managers, assistants and everyone in your practice to understand how they contribute to better patient care.

By: Kevin Huff

Date: September 6, 2016

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts