Where's the Overjet: Why Veneers Are Breaking Off

By Steve Ratcliff on December 3, 2015 |Every dentist has faced a case that fails and the reason isn’t immediately clear. The patient is disappointed and the dentist doesn’t feel good about letting the patient down. Sometimes we may not even know why the case failed or what to do to prevent the issue from recurring.

Sometimes the case isn’t our own and we are faced with unraveling the puzzle and creating a workable solution for the patient.

Then we are often faced with the other tough question ... Why didn’t my previous dentist do this?

Using a current case that I am working on so I can talk to my patient, I’d like to walk through my take on both issues - the technical and the behavioral.

"Doc, My Veneers Keep Popping Off!"

This 32-year-old patient presents with a complaint that his veneers keep popping off. (Figures 1 & 2) He has some awareness of clenching when under stress, and perhaps at night. He has popped three veneers, all on the left side. There is evidence of wear on the palatal surfaces of both maxillary canines, and to a lesser extent the maxillary incisors. He also had orthodontics as a teenager.

About six years ago, he wanted whiter and longer teeth. Veneers were placed from first premolar to first premolar, upper and lower; two years in, they started to break.Three of the veneers have shattered and been temporarily replaced with composite. There is staining around many of the facial margins of the veneers and on the lingual and palatal. Additionally, there is proximal decay between some of the anterior teeth and several of the posteriors.

So in brief, we have a patient who has teeth that were lengthened with veneers and now the veneers are breaking and popping off. There is evidence of wear and his home care and diet have resulted in areas of decay.

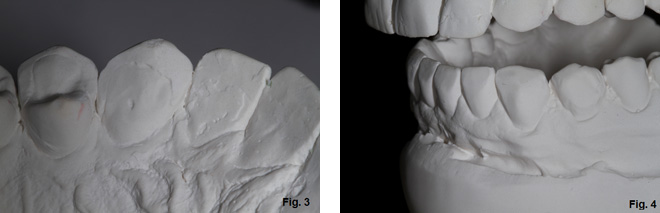

The clinical issue is one reason why the veneers look the way they do, and could be the reason that the veneers keep breaking and debonding. If you look at the next two images, you will notice the wear on the palatal of the upper canine and the lingually inclined contours of the lower anteriors. (Figures 3 & 4)

When there is evidence of wear on the facial of lower anteriors or the restorations have anatomy that is altered to make them fit, and there is accompanying wear on the palatal surfaces of the upper anteriors, the etiology is generally interference with the functional pathway and the patient is “locked” in. Simply put, there is not adequate overjet.

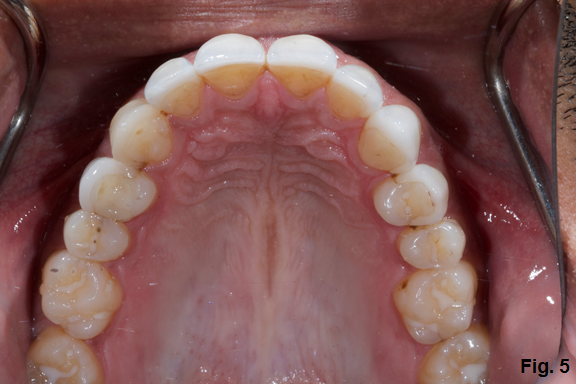

Additionally, if you look at his posterior teeth, you will notice that he doesn’t have much wear behind the canines. (Figure 5)

The 4 Ways to Treat Pathway Wear:

- Move the teeth to create more overjet

- Open the vertical dimension of occlusion

- Orthognathic surgery to move an arch

- Selectively remove tooth structure to create more overjet

At Spear, we teach a process called Facially Generated Treatment Planning that is a linear and very accurate method of creating a diagnosis and a treatment plan. We evaluate four categories: esthetics, function, structure and biology (EFSB). We use these categories to create the possible outcomes for the patient.

(Click here for more on EFSB.)

In this case before we decide on a treatment option, we need to look at the patient and begin with the maxillary central incisors. Are they in the correct position relative to appropriate esthetics and function? If you look at Figure 1, the patient’s smile isn’t bad, the tooth length is adequate and the midline is appropriate. Other than perhaps lengthening the left canine, not much change is needed. The lower anteriors are different, though. They are mishapened and bulky and could look better.

Next we look at function; we already know that there is wear, and that he knows that he clenches and possibly grinds. We also know that there is very little wear on the back teeth, which means he probably is not grinding at night - but that doesn't rule out clenching. There is fremitus of the anteriors when the patient taps his teeth together, meaning there is slight mobility. We know that we need more overjet to create better function.

Now, we look at the structure of the teeth to consider the mechanics of any restorative process. In this case, he has 16 ceramic restorations at a young age, so keeping things as conservative as possible is important. Also, trying to avoid prepping any unprepped teeth would be to his long-term benefit.

Finally, we need to address his caries rate. He has a total of eight interproximal lesions that must be treated, which means he will also benefit from learning how to manage his home care and his diet. Additionally, there is visible calculus between his posterior teeth on his bitewings, so his tissue health is not good enough for excellent final restorations.

Following EFSB Makes Treatment Planning Easier

Opening vertical dimension of occlusion will be the easiest and fastest way to gain overjet. However, if that option is chosen, it means that all the remaining posterior teeth that have not been prepped will now have to be restored. At the age of 32, that commits him to 28 restorations for the rest of his life. This is probably not a good choice.

Orthognathic surgery is the least favorable option in this case. Although he has a transverse discrepancy and has end to end posterior occlusion, there are easier and less invasive ways to give him overjet. (Figure 6)

Selectively removing tooth structure might be a possibility in this case. The lower veneers appear to be very bulky and if removed, there might be more room than there appears. Combined with some selective recontouring of the palatal surfaces, the result could work. However, there is already wear on the palatal surfaces and reducing the tooth structure could mean that the reduction could end up exposing palatal dentin.

Moving teeth would mean considering the labiolingual inclination of the upper anteriors, as well as the same position of the lowers. If we look at the angle of the upper incisor to the occlusal plane in Figure 6, the inclination of the incisors could be increased slightly. In the lower arch, the lower anterior could be retracted slightly with some interproximal reduction and create the overjet needed to redo the case.

My preference in this case would be the orthodontic option; I think it is the most stable long-term result. However, the patient has to agree, and that often is the hardest part of dentistry.

I have learned over the years that I can’t get too attached to what I think is the best solution. It really isn’t hard to talk to patients about treatment as long as we remember that our job is to present the options, discuss the risk and benefits of each option and the implication of no treatment. Then you can let the patient choose.

Some clinicians believe that there is only one best treatment plan; my belief is that there are often many treatment plans and what is best is defined by the patient’s circumstances, temperament and objectives.

(Click here for a subtle yet simple way to improve dental treatment acceptance rates.)

If the patient makes a decision to not accept treatment or insists on treatment that I do not feel comfortable with, I always have the choice to not participate. However, no doesn’t mean no forever. It may simply mean not now.

When I discuss the case with the patient, I will talk about all of the options I see. I will do my best to make sure he understands the pros and cons of each. Then I will not be surprised if he asks me what I would do. That frequently happens when you give people choices; they let you offer your opinion about what is best. They do this because they haven’t been sold and they are now asking you to be the doctor. That’s a good day.

(If you enjoyed this article, click here for more content from Dr. Steve Ratcliff.)

Steve Ratcliff, D.D.S., M.S., Spear Faculty and Contributing Author

FREE COURSE:

Managing Compromised Occlusions

Now that you've read about dealing with overjet issues, learn more about treating other occlusal issues. This free course, "Managing Comprosmised Occlusion," will help you be prepared when occlusal compromise needs to be part of the solution.

WATCH NOW