Dentistry's Battle With the Inferior Alveolar Nerve

By Kevin Kwiecien on May 29, 2015 | Is it worth the battle? Or should we just raise the white flag and admit defeat? Do we have any hope for victory? Can we uncover a weakness in the opponent? If you feel like the odds are against us, would you be open to the possibility that with more focused training, skill refinement and the ability to change up our strategy when needed, that we could actually win the war?

Is it worth the battle? Or should we just raise the white flag and admit defeat? Do we have any hope for victory? Can we uncover a weakness in the opponent? If you feel like the odds are against us, would you be open to the possibility that with more focused training, skill refinement and the ability to change up our strategy when needed, that we could actually win the war?

Sometimes, all we need is hope. After almost 20 years (and counting) of missing my share of mandibular injections and many years in academia, somewhat hypocritically, trying to convince students that they really can have more predictable success – I thought it might be nice to build on some positive momentum and provide some proof for all of us that we are actually mounting a comeback together. Intuitively, I knew it was true because I have been reading the literature for years, hoping for the big break that was going to completely end my misery, and critically evaluating the trends along the way. Experientially, I noted positive changes that were the result of more than just good luck and playing the odds. But to prove my point and share the hope, I thought it would be nice to review the current literature (2010 to 2014), focusing on the rationale behind our hope and behind our continued struggles, with respect to the following: chemistry, anatomy and technique.

Advantage #1: Chemistry

Understanding the Chemical Choice and Possible Chemical Alteration

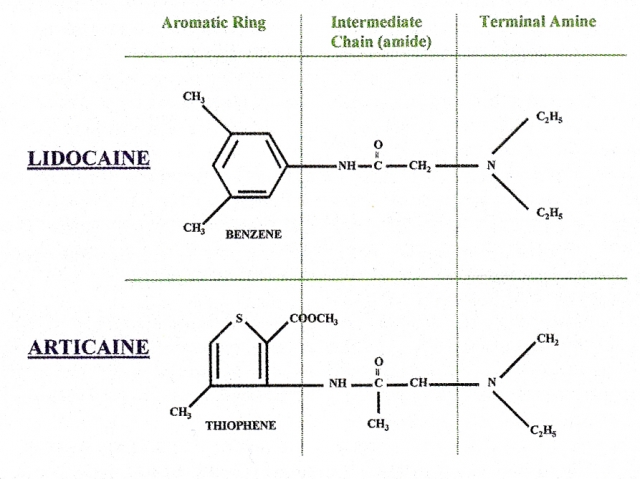

In a recent short article, I shared an update on the evolution of Articaine in daily practice. As you know, there has been some hesitation and controversy surrounding the use of this anesthetic. A 2010 article outlines a wonderful meta-analysis comparing the efficacy and safety of Lidocaine and Articaine.(1) It was found that Articaine was more likely to achieve anesthetic success for routine dental procedures and that both drugs appear to have similar adverse effect profiles. The article summarizes that Articaine is a superior anesthetic for use in routine dental procedures. Use in children under four years of age is not recommended, since no data exists to support such usage.

A similar 2011 article outlining another meta-analysis compares the pulpal anesthetic efficacy of Articaine and Lidocaine.(2) Articaine solutions had a probability of achieving anesthetic success superior to that of Lidocaine. The greater odds ratio for Articaine actually increased when the authors analyzed only infiltration data. There was weaker, but still significant, evidence of Articaine being superior to Lidocaine for mandibular block anesthesia.

Buffering

A relatively recent trend that seems to be building momentum is the process of alkalinizing Lidocaine to increase the onset time. Conveniently, it also seems to decrease the discomfort routinely associated with injecting Lidocaine, due to the acidic pH. A 2013 article by Malamed et al., comparing latency and injection pain in inferior alveolar nerve blocks using alkalinized and non-alkalinized Lidocaine, supports the addition of a new “sneak attack” to our strategy.(3)

With the alkalinized anesthetic, 71 percent of participants achieved pulpal analgesia in two mnutes or less. With non-alkalinized anesthetic, 12 percent achieved pulpal analgesia in two minutes or less. The average time to pulpal analgesia for the non-alkalinized anesthetic was 6:37 (range 0:55 to 13:25). Average time to pulpal analgesia for alkalinized anesthetic was 1:51 (range 0:11 to 6:10). The obvious conclusion and assumption that we might start to trust is that alkalinizing Lidocaine (1:100,000) toward physiologic pH immediately before injection significantly reduces anesthetic onset time and increases the comfort of the injection.

Advantage #2: “New” Anatomy Variability

Understanding Recent Anatomic Considerations

We have the option of ignoring common trends, or even the not-so-common trends, in anatomic variation and using those variations as an excuse when results are not consistent. Or we can have an understanding and appreciation for the realistic possibilities. We can then make educated guesses based on those, thereby intentionally changing our approach with some rationale behind it. Minimally, we’ll probably feel a little better and smarter when some struggles continue. Optimally, we’ll see consistent improvements in results that provide positive reinforcement for continued curiosity and knowledge.

Historically, we have confirmed that accessory innervations from the mylohyoid and mental foramen contribute to the inability to achieve profound anesthesia in the posterior mandibular dentition. So, we now routinely infiltrate in those areas, which certainly have improved our results. Imagine how tough it was on the patient and the dentist, physically and mentally, before anatomists linked our unpredictable outcomes with those accessory innervations.

A 2013 article outlines the potential accessory innervation of posterior mandibular teeth from the transverse cervical nerve, a branch of ventral rami from the C2-C3 spinal nerves from the cervical plexus.(4) Lin et al note that previously it has been difficult to assess, as a result of the small size and thickness of the mandibular accessory foramina and nerve branches, as well as due to the dissection technique performed. They used a specific dissection technique (Sihler’s technique) that helps disclose structures of small size and thickness. The results confirmed that the transverse cervical nerve from the cervical plexus did innervate the posterior mandible in one of the two samples. These findings illustrate variations of anatomy that may account for inferior alveolar nerve block failures in posterior mandibular teeth and allows for clinical decisions for implementing supplemental anesthetic techniques.

Advantage #3: Anatomic Reality

Appreciating the Difficulty Even Without Variability

Sometimes it just makes us feel better if we are struggling with something we know is hard, especially when we know that we have zero chance at achieving consistent success. In a 2011 supplemental article in the Journal of the American Dental Association, Malamend confirmed our daily sentiment, remarking that “achieving consistently reliable anesthesia in the mandible has proved elusive. The traditional inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) has a high failure rate.”(5) He suggested that the reasons for this high failure rate include thickness of the cortical plate of bone in adults, thickness of the soft tissue at the injection site leading to increased needle deflection, the difficulty of locating the inferior alveolar nerve, and the possibility of accessory innervation.

Again, imagine how it was many years ago when our profession did not fully understand and appreciate the difficulty. When we at least know our opponent and understand its strengths and it’s strategies to defeat us, we can at least offer ourselves some grace and some space to try again with dignity and hope. However, when we do try again, it is important to use the “intel” noted from scouting our opponent to our advantage, which brings us to the next advantage.

Advantage #4: Anatomic Reality Part 2

Appreciating Common Anatomic Variations

A 2011 article serves as a nice reminder that the pterygomandibular space has not changed (imagine that!) and that a deep understanding of the anatomy can increase our odds of success, stating that, “A thorough knowledge of the anatomy of the pterygomandibular space is essential for the successful administration of the inferior alveolar nerve block. In addition to the inferior alveolar and lingual nerves, other structures in this space are of particular significance for local anaesthesia, including the inferior alveolar vessels, the sphenomandibular ligament and the interpterygoid fascia. These structures can all potentially have an impact on the effectiveness of local anaesthesia in this area. Greater understanding of the nature and extent of variation in intraoral landmarks and underlying structures should lead to improved success rates, and provide safer and more effective anaesthesia.”(6)

Additionally, a higher than normal position of the mandibular foramen has been demonstrated on a fairly consistent basis. A 2014 case report that I will reference again when addressing injection techniques serves as a reminder that, “The inferior alveolar nerve block is one of the most common techniques for delivering dental anesthesia. Its success depends on placing the needle tip in close proximity to the mandibular foramen (MF). In certain cases, however, this nerve block fails, even when performed by the most experienced clinician. Anatomical variability may be one source of local anesthetic failure and includes bone and nerve variations. A case is presented of a bilateral anomalous high position of the MF, identified from the panoramic radiograph.”(7)

With this information, you might be considering playing the odds and erring higher than lower on a routine basis when administering an inferior alveolar never block. A 2014 article by Montserrat-Bosch et al, comparing the conventional Halsted technique to a more inferior injection point would support your tactic.(8) The modified technique (inferior location) group showed a significantly higher onset time in the lower lip and chin area and was frequently associated to a lingual electric discharge sensation. Additionally, they found that performing an inferior alveolar nerve block in a more inferior position, modified technique, extends the onset time, does not seem to reduce the risk of intravascular injections and might increase the risk of lingual nerve injuries.

Advantage #5: Alternative Techniques Part 1:

Arched Needle

I always find it interesting when an old technique resurfaces in the literature. What does that tell us about the constant and continued struggles? I also can’t help but to wonder what it tells us about the comfort level of dentists to try something different without the direct support or even supervision of a more experienced clinician, especially when it comes to injection techniques. A 2013 article reported that the traditional, Fischer’s technique, inferior alveolar nerve block suffers maximum failure rate of approximately 35 to 45 percent.(9) Using an arched needle technique by injecting a local anesthetic solution into the pterygomandibular space by arching and changing the approach angle of the conventional technique in a manner that it approaches the medial surface of the ramus at an angle almost perpendicular to it, resulted in a 98 percent success rate, based on adequate anesthetic effects for mandibular molar extraction.

Advantage #6: Alternative Techniques Part 2:

Vazirani-Akinosi

Similar to the arched needle technique, the Vazirani-Akinosi technique, also known as the closed mouth technique, for anesthetizing the inferior alveolar nerve, seems to resurface on a regular basis. I think it would be beneficial to point out that the message is not to avoid it. On the contrary, it is a reminder of another tactic that we could be using. I have a hunch that the lack of implementation for this technique is directly related to the comfort level, not the results.

The previously referenced 2014 case report demonstrating the high position of the mandibular foramen documented “an adjusted anesthetic technique” (the Vazirani-Akinosi technique) was used to achieve local anesthesia before extraction of a lower second molar following an unsuccessful conventional indirect technique with a higher entry point.(7)

A 2012 article referred to it as an “under-utilized mandibular nerve block technique.”(10) This retrospective study, conducted in a self-referral clinic, included patients treated between January 1993 and December 1995. Of the 480 patients that were treated with block anesthesia, 392 (81.7 percent) were treated with standard technique while only 88 (18.3 percent) were treated with Akinosi technique. Interestingly, even this group of surgeons chose this traditional technique in spite of the reported higher merits of Akinosi techniques. I challenge you to think and act differently from those surgeons, with the confidence that the literature supports your efforts and process.

Advantage #7: Alternative Techniques Part 3:

Gow-Gates

Similar to Akinosi, the Gow-Gates technique is a tactic in our strategy that might not make it to the battlefield often enough. It also resurfaces in the literature with continued research and case studies supporting the use as an alternative to traditional inferior alveolar techniques.

A 2013 split-mouth study in China, consisted of 32 participants scheduled for bilateral extraction of impacted third molars.(11) Each side was randomly picked for either the Gow-Gates technique and the other side for traditional technique. The anesthetic success rate was 96.9 percent in Gow-Gates group and 90.6 percent in conventional group with no statistical difference ( P= 0.317); but when comparing the anesthesia grade, Gow-Gates group had a 96.9 percent of grade A and B, and conventional group had a rate of 78.1 percent (P = 0.034). Neither group experienced a hematoma. Yang et al concluded that Gow-Gates technique had a reliable anesthesia effects and safety and “could be chosen as a candidate for the conventional inferior alveolar nerve block.”

I have alluded to the possibility that alternative block techniques often resurface in the literature and that it is likely do to the hesitation of dentists to use them while they continue to suffer the consequences of not using them. Is it the lack of trust? Lack of confidence? Lack of understanding? A 2011 article in the Journal of the American Dental Association by Haas reminds us that the limited success rate of the standard inferior alveolar nerve block is what led to the development of alternative approaches for providing mandibular anesthesia.12 The article specifically states that, “Two techniques, the Gow-Gates mandibular nerve block and the Akinosi-Vazirani closed-mouthmandibular nerve block, are reliable alternatives to the traditional IANB,” and that, “Both techniques are indicated for any type of dentistry performed in the mandibular arch, but they are particularly advantageous when the patient has a history of standard IANB failure owing to anatomical variability or accessory innervation.” Sounds pretty straight forward to me. Haas concludes that, “Having the skill to perform these alternative anesthetic techniques increases dentists' ability to provide successful local anesthesia consistently for all procedures in mandibular teeth.”

Advantage #8: Alternative Techniques Part 4:

Skip the Nerve!!

Finally, the original sneak attack, which has become somewhat routine, takes some of the mystery out of the process. Maybe we can’t really skip the nerve entirely, but the intraosseous injection is certainly a viable adjunct to any of the block techniques. A 2012 simple-blind, prospective clinical study study of 100 patients who were anesthetized bilaterally with conventional and intraosseous techniques compared latency period, anesthesia sensation, and duration concluded that intraosseous anesthesia has been shown to be a technique to be taken into account when planning conservative treatments.(12)

And in 2014, a clinical study by Idris et al demonstrated the benefit of using intraosseous injection as an adjunct to conventional techniques.(13) Sixty adult patients selected were to undergo endodontic treatment for a mandibular molar tooth. Inferior alveolar nerve block was given using 4 percent Articaine with 1:100,000 Epinephrine. Twenty-four patients (40 percent) had pain even after administration of the block. Intraosseous injection was administered using 4 percent Articaine containing 1:100,000 Epinephrine, using the X-tip system. Out of the 24 patients who were given the supplemental X-tip injection, 21 were successful. Supplemental intraosseous injection using 4 percent Articaine with 1:100,000 Epinephrine has a statistically significant influence in achieving pulpal anesthesia in patients with irreversible pulpitis.

The eight “advantages” listed above can really be condensed into three categories: chemistry, anatomy and technique. If we optimize our strengths and understand our “opponent,” we have the opportunity to create two critical results: First, we will undoubtedly see more consistent improved results and we might even win the battle. Second, and probably more important, we can offer ourselves some much deserved grace and feel confident and competent even in the face of defeat.

References

- J Dent. 2010 Apr;38(4):307-17. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2009.12.003. Epub 2009 Dec 16. The efficacy and safety of articaine versus lignocaine in dental treatments: a meta-analysis. Katyal V.

- J Am Dent Assoc. 2011 May;142(5):493-504.The pulpal anesthetic efficacy of articaine versus lidocaine in dentistry: a meta-analysis. Brandt RG1, Anderson PF, McDonald NJ, Sohn W, Peters MC.

- Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2013 Feb;34 Spec No 1:10-20. Faster onset and more comfortable injection with alkalinized 2% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000. Malamed SF1, Tavana S, Falkel M.

- Clin Anat. 2013 Sep;26(6):688-92. doi: 10.1002/ca.22221. Epub 2013 Jan 29. Transverse cervical nerve: implications for dental anesthesia. Lin K1, Uzbelger Feldman D, Barbe MF.

- J Am Dent Assoc. 2011 Sep;142 Suppl 3:3S-7S. Is the mandibular nerve block passé? Malamed SF.

- Aust Dent J. 2011 Jun;56(2):112-21. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01312.x. Applied anatomy of the pterygomandibular space: improving the success of inferior alveolar nerve blocks. Khoury JN1, Mihailidis S, Ghabriel M, Townsend G.

- Surg Radiol Anat. 2014 Aug;36(6):613-6. doi: 10.1007/s00276-013-1209-y. Epub 2013 Sep 25. Bilateral anomalous high position of the mandibular foramen: a case report. Cvetko E.

- Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2014 Jul 1;19(4):e391-7. Efficacy and complications associated with a modified inferior alveolar nerve block technique. a randomized, triple-blind clinical trial. Montserrat-Bosch M1, Figueiredo R, Nogueira-Magalhães P, Arnabat-Dominguez J, Valmaseda-Castellón E, Gay-Escoda C.

- J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2013 Mar;12(1):113-6. doi: 10.1007/s12663-011-0310-1. Epub 2011 Oct 19.Arched needle technique for inferior alveolar mandibular nerve block. Chakranarayan A1, Mukherjee B2.

- Niger J Med. 2012 Jan-Mar;21(1):89-91.Akinosi (tuberosity) technique: a verity but under-utilised mandibular nerve block technique. Mgbeokwere U.

- Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2013 Aug;31(4):381-4. [The anesthetic effects of Gow-Gates technique of inferior alveolar nerve block in impacted mandibular third molar extraction].[Article in Chinese] Yang J1, Liu W, Gao Q.

- 12.Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012 Mar 1;17(2):e233-5. Comparative study between manual injection intraosseous anesthesia and conventional oral

- J Conserv Dent. 2014 Sep;17(5):432-5. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.139828. Intraosseous injection as an adjunct to conventional local anesthetic techniques: A clinical study. Idris M1, Sakkir N2, Naik KG3, Jayaram NK1.

FREE COURSE: Mandibular Nerve Blocks

Now that you've read about the advances in nerve blocks, learn even more about the mandibular nerve block. In this free course, "Mandibular Nerve Blocks: Part 1," you will get insight into needle choice, nerve block goals and how to trouble-shoot failures. Click below to get started for free!

Watch Course