Drive Time: Why Implant Drivers Are So Important

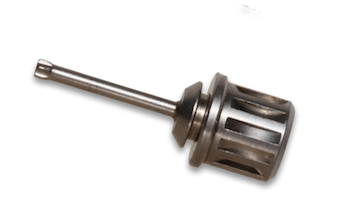

In implant dentistry hand drivers are used to turn the attachment or abutment screws that secure different components to implant fixtures. Hand drivers are similar to a screwdriver that you may have in the garage, but way smaller. Implant hand drivers include a handle, shaft and patterned tip.

The handle will usually have a surface texture to prevent it from being easily dropped, and a small hole, through which one could tie a ligature. These drivers are pretty small so it’s a good idea to use that feature as well as placing a gauze throat pack.

Dropping drivers, screws and abutments are an all too real problem. The handle will also usually nest into a torque wrench, allowing the clinician to deliver a controlled amount of force to the screw.

The shaft connects the handle to the tip. Hand drivers are available with shafts of varying length. If they’re too short you can’t reach the screw head or get around adjacent teeth; too long and you collide with the opposing arch. These shafts have to be strong enough to withstand the forces placed on them while applying torque to the attachment screws.

The tip of the hand driver is the portion which engages the pattern in the attachment screw. This pattern varies by implant manufacturer. Some manufacturers use a standard slot or a hexagon while others use a different geometric configuration. It is this pattern that makes a driver specific to an implant system. As a result, clinicians will need to have on hand at least one set of drivers for each implant system they anticipate encountering in practice.

So far I have described general characteristics of clinical hand drivers; however, it’s important to consider lab drivers as well. Lab drivers maintain the same anatomy and specificity as the clinical drivers but since we generally use them on a cast, the handles can be much larger. This makes lab drivers easier to keep track of in the lab and easier to use when fabricating restorations (provisional or definitive) that will have to go on and off the cast multiple times.

Sometimes we can use lab drivers clinically. Often with maxillary restorations, but occasionally even with mandibular restorations, the angle needed to access the attachment screw will allow a lab driver to be used to turn the screw. I have found this especially useful with maxillary full arch prostheses.

Bear in mind that it is possible to deliver a lot more torque to the attachment screws so we have to be careful not to over tighten. If you decide to use a lab driver clinically, it’s important to use a design that can be sterilized afterward.

Darin M. Dichter, DMD, Spear Visiting Faculty.

FOUNDATIONS MEMBERSHIP

New Dentist?

This Program Is Just for You!

Spear’s Foundations membership is specifically for dentists in their first 0–5 years of practice. For less than you charge for one crown, get a full year of training that applies to your daily work, including guidance from trusted faculty and support from a community of peers — all for only $599 a year.

By: Darin Dichter

Date: February 12, 2014

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts