Muscle Deprogramming: A Source of Confusion

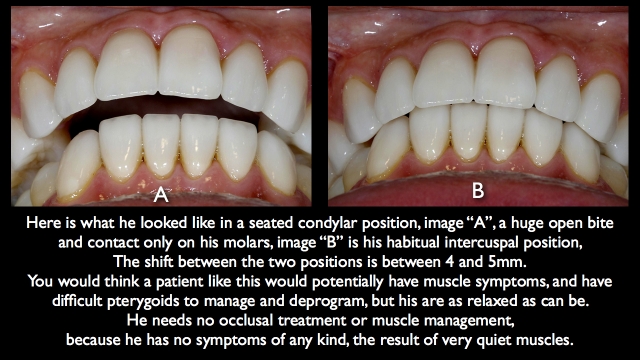

Muscle deprogramming is simple in concept, but may be confusing in execution. Why? There are variations between individuals regarding the way their muscles respond and because the same individuals may respond differently on different days. The purpose of muscle deprogramming is generally to reduce or relax muscle activity levels to eliminate muscle pain, tension or discomfort. This now allows for an accurate examination of the relationship of the maxilla to the mandible with the muscles relaxed and the condyles in a fully seated position.

Let’s Talk About Muscle Deprogramming

The muscle that frequently prevents condylar seating is the lateral pterygoid – which is programmed to position the mandible to avoid pain and posterior interferences in the arc of closure. Deprogramming generally is done by placing something in the anterior that eliminates posterior occlusal contact like a Lucia jig, leaf gauge, bite plane, etc.

This lack of posterior occlusal contact is now thought to allow the lateral pterygoid to release, since it no longer has to hold the mandible in an anterior or lateral position to avoid posterior tooth contacts. In addition, the contraction of the elevator muscles should aid in the stretching of the lateral pterygoids, as the elevator muscles want to seat the condyles when they contract.

All is simple and good, and most patients behave exactly as predicted – but some do not. What deprogramming can’t control is the other stimuli sent to the lateral pterygoid muscle. An example may be a nocturnal bruxer; they are sleeping comfortably, the teeth are apart, the pterygoids relaxed, they have an anterior bite plane in place but suddenly their sympathetic nervous system activates, arousing a cascade of events affecting their heart rate, brain activity and ultimately muscles. At that point the pterygoids go into hyper drive, moving the mandible, left, right, forward – even though the deprogrammer is in place. Several things could stimulate the sympathetic nervous system to start the cascade of events, airway issues, gastric reflux, emotional stress and other less clear possibilities.

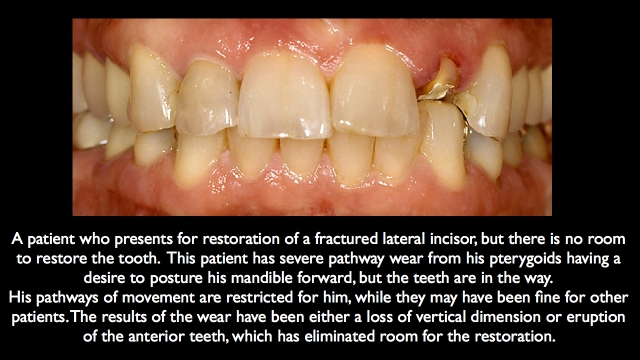

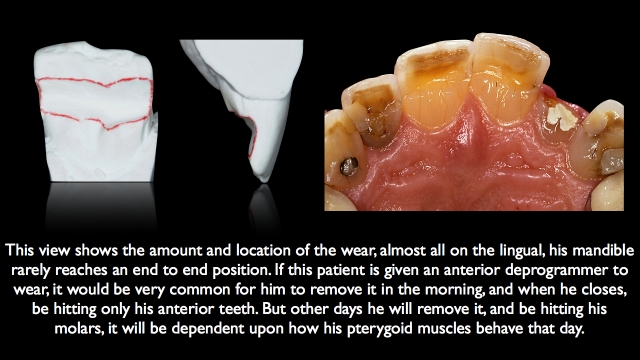

These patients typically do show signs or symptoms on their anterior teeth. These may include significant lingual wear of the maxillary anterior teeth, wear on the facial of mandibular anterior teeth and mobility or migration of the maxillary anteriors is a possibility.

The bruxing example is one example that could occur, and daytime bruxism is another. In these patients, deprogramming is very difficult, and in some, next to impossible. Most dentists have had a patient show up at the office who woke up that morning unable to bite on their back teeth even though they claim their bite was fine when they went to bed last night. In some, it even hurts to try and close on the back teeth. What is going on? Their lateral pterygoids are in spasm, stuck in a contracted state.

What Do We Do Now?

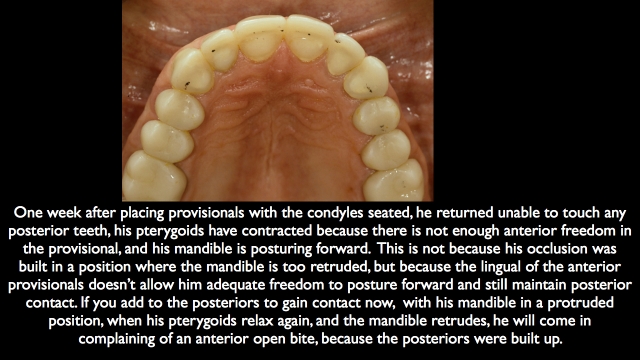

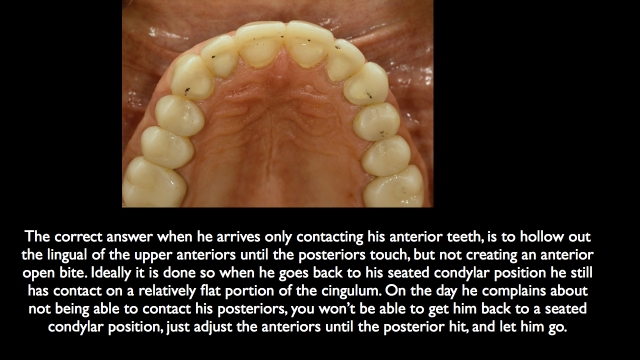

Your first thoughts are to make them an anterior deprogrammer to help the pterygoids release – but they already have one. Currently they are only touching their anterior teeth, and their anterior teeth are acting as a deprogrammer while there is no posterior contact. Why doesn’t the lack of posterior contact deprogram the lateral pterygoids? Because the signal they are getting to contract is overriding any mechanical deprogramming that would occur from a lack of posterior occlusion.

Interestingly enough, if you give the patient in this situation an Aqualizer, a posterior only appliance, it not only provides some comfort, but in a day or two their occlusion typically returns to normal as the pterygoids release and allow the mandible to retrude.

If these patients need significant dentistry, you have to be very careful. If you give them an anterior only appliance, such as an NTI or anterior bite plane for deprogramming, we expect their condyles to seat and their mandible to retrude. Instead they may end up contacting only their anterior teeth after removing the appliance one day, and only their posterior teeth after removing the appliance the next day.

One helpful aid for these patients is to have them keep a log. Every morning after they first remove the appliance, ask them to record where they feel the teeth hit first, front or back. If the posteriors hit first, the pterygoids probably released and are acting normally. If the next day the anterior teeth hit first, the pterygoids didn’t release with the deprogramming, they were stimulated to remain active. If you have a patient that has a log of multiple different answers (ie. out of 14 days, 10 times they were on their front teeth, and four times on their back teeth). Now you have a problem.

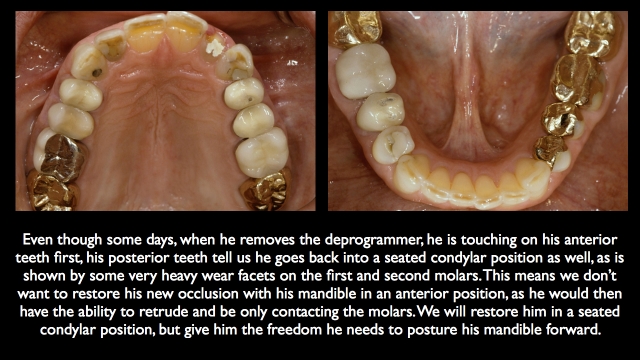

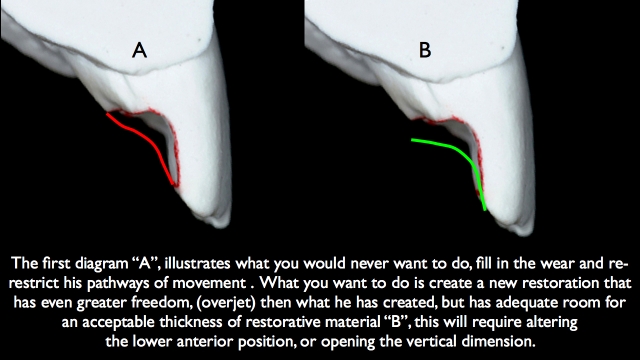

The temptation is to think that this patient needs you to build their intercuspal occlusion in a more forward position to accommodate the findings on the bite plane (ie. most of the time they were forward when they took the appliance out). But this has a problem. The other days they took the appliance out, the condyles were seated and they were on their back teeth. If you build their intercuspal occlusion in a forward position, now when the pterygoids release and the mandible goes back, you have no control over which teeth become posterior interferences and what they may do to those teeth.

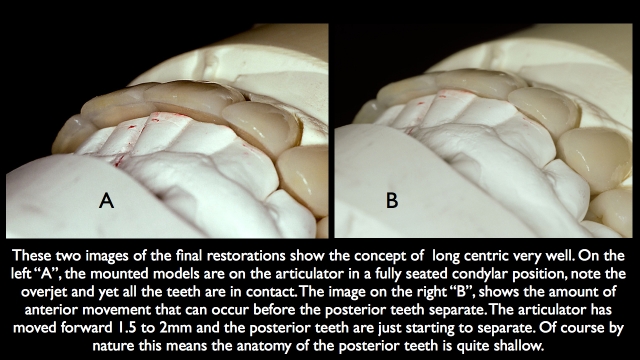

The answer is that these unpredictable patients typically need their intercuspal occlusion created in a fully seated condylar position. Assuming they go there on the deprogrammer without pain, but then they need a tremendous amount of freedom to move forward while still maintaining posterior occlusal contacts before there anterior guidance takes over in essence, what may be thought of as a long centric.

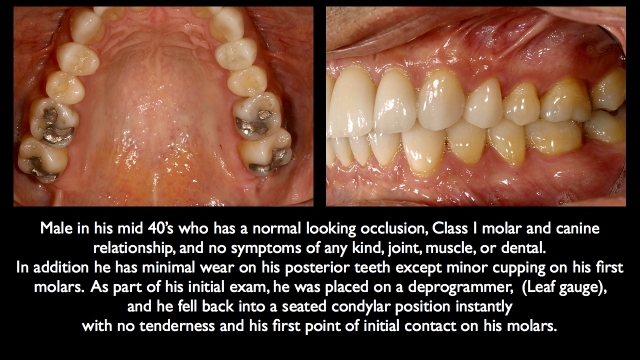

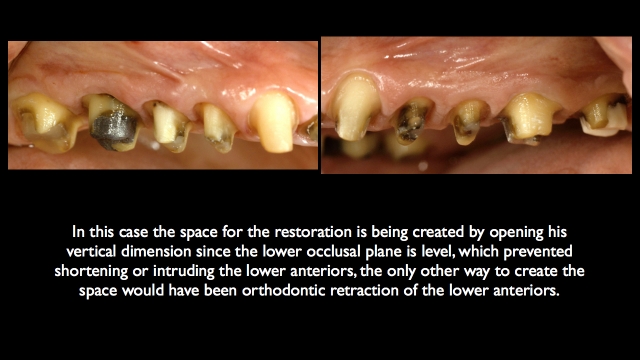

Look at the Wear on the Patient’s Teeth

These patients will typically show you evidence that they need this occlusion by the wear on their teeth. Heavy wear on first and second molars will show you they go back into a seated condylar position and parafunction there; heavy lingual wear on the maxillary anterior teeth and wear on the facial of mandibular teeth tells you they need greater anterior freedom of movement.

These are also patients where making your bite records using a flat deprogrammer such as a Lucia jig, or flat anterior stop has risks. This is due to the fact that it is very easy for them to bite forward on the deprogrammer and you perceive that as the position to build their intercuspal occlusion, when in reality, that may be showing you the position they need their anterior freedom of movement built to. My preference is to use a leaf gauge to make the bite record, assuring less risk of them posturing forward.

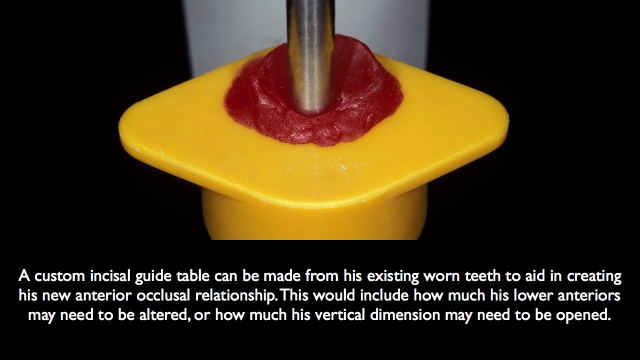

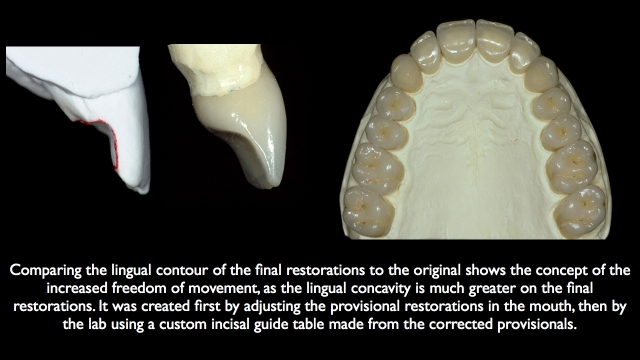

Then make a custom incisal guide table from their mounted models using their existing pattern of wear to aid in setting up the anterior occlusal relationship and assuring adequate freedom of movement. Ultimately the provisional restoration becomes the testing ground to assure your anterior functional relationship is acceptable.

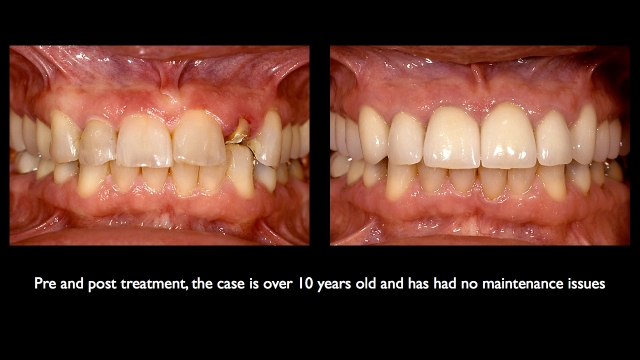

The good news is that this is not a large group of patients. In other words, most patients deprogram as expected, and the lateral pterygoids release as expected – but this patient, when encountered, is a difficult patient to manage, as their pterygoid activity can wreak havoc on restorative dentistry, especially on top of implants.

Lastly, if you are getting anterior points of contact frequently in normal patients after deprogramming, be aware of how you are getting the patient to close. For example, if you used an anterior bite plane, Lucia jig or any flat anterior stop, if you remove it and say bite, you may get a significant number of patients who close on their anterior teeth. If on the other hand you ask the patient to slide forward on the deprogrammer, then back, now try and squeeze on your back teeth, now open, remove the deprogrammer, and instruct them to let their jaw go back and close on your back teeth, you will find very few patients will posture forward.

References

Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 2004 Sep;12(3):125-8. Reliability of a measuring-procedure to locate a muscle-determined centric relation position. Zonnenberg AJ, Mulder J, Sulkers HR, Cabri R.

Angle Orthod. 1999 Apr;69(2):117-24; discussion 124-5. The use of a deprogramming appliance to obtain centric relation records. Karl PJ, Foley TF.

Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006 May;129(5):619-30. Three-dimensional analysis of models articulated in the seated condylar position from a deprogrammed asymptomatic population: a prospective study. Part 1. Cordray FE.

J Prosthet Dent. 1988 May;59(5):611-7. Simple application of anterior jig or leaf gauge in routine clinical practice. Carroll WJ, Woelfel JB, Huffman RW. Department of Restorative and Prosthetic Dentistry, Ohio State University, College of Dentistry, Columbus.

Dent Clin North Am. 2012 Apr;56(2):387-413. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2012.01.003. Sleep bruxism: a comprehensive overview for the dental clinician interested in sleep medicine.

Carra MC, Huynh N, Lavigne G.

SPEAR campus

Hands-On Learning in Spear Workshops

With enhanced safety and sterilization measures in place, the Spear Campus is now reopened for hands-on clinical CE workshops. As you consider a trip to Scottsdale, please visit our campus page for more details, including information on instructors, CE curricula and dates that will work for your schedule.

By: Frank Spear

Date: September 7, 2015

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts