TMJ Imaging, Part 2: Examining a Clinical Case

In my previous Spear Digest article, we discussed when to consider obtaining TMJ imaging. Specifically, we reviewed two key questions to determine if we should consider TMJ imaging with MRI and CBCT.

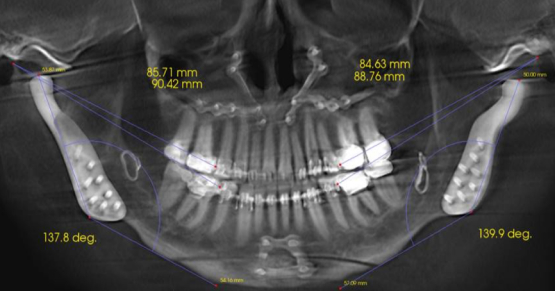

- Does the patient have pain greater than five on a 1-10 scale?

- Are the teeth uncoupled greater than the thickness of the disc?

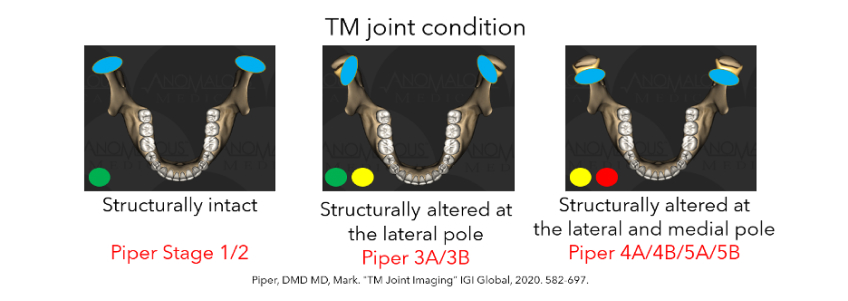

If either one or both questions are yes, it increases the likelihood that one or both TMJs are structurally altered at the lateral and medial poles. Examining a clinical case can help to clarify the process.

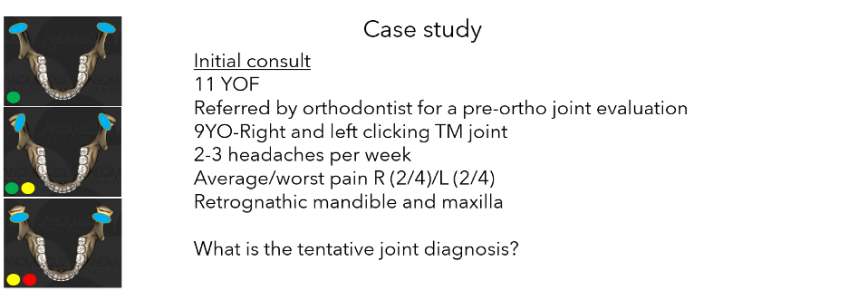

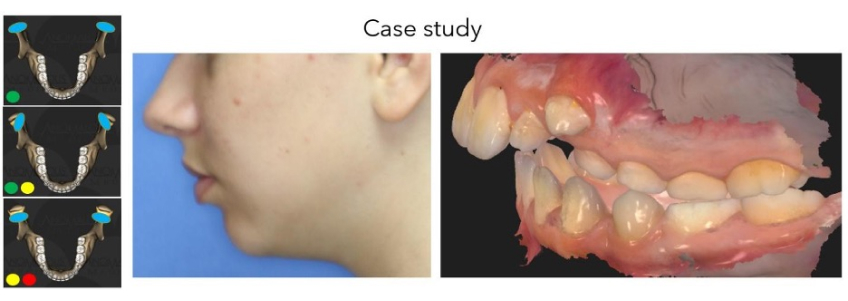

A TMJ clinical case study

A clinical case can help us understand the concepts outlined above. Below outlines the details of an 11-year-old patient referred by an orthodontist for a pre-ortho joint evaluation.

If the orthodontist is referring the patient for a TMJ evaluation before beginning orthodontic treatment, there is an increased likelihood the patient has SA-LP/MP (structurally altered at the lateral pole and medial pole).

A clicking joint means there is a ligament tear in the TMJ. Once we determine that there is a ligament tear, the next step is to determine whether the ligament tear is located at the lateral pole or the medial pole.

My clinical experience, along with peer-reviewed literature, indicates that there are significantly more structurally altered TMJs in growing patients than previously expected. In 2011, Sylvester wrote, “Out of the 38 patients who were excluded in our study, 28 were younger than 16 years old. This indicates that internal derangement of the TMJ also occurs in young populations. Patients are in their growing stages, and their articulations are supposed to tolerate stress due to their remodeling potential; however, they show chronic articular alteration, which may affect them for a lifetime.”

In 1993, Schellhas wrote about “the high percentage of evidence of TMJ abnormality from imaging studies could mean that the problem is more widespread than previously recognized. Since orthodontists do not routinely study the temporomandibular joint status of patients, the possibility exists that the specialty is not aware of the pervasiveness of the problem.”

The fact that there is pain regularly, along with two headaches per week, increased the likelihood of SA-LP/MP TMJs. Growing patients should not have TMJ pain, and if they do, it should warrant further investigation.

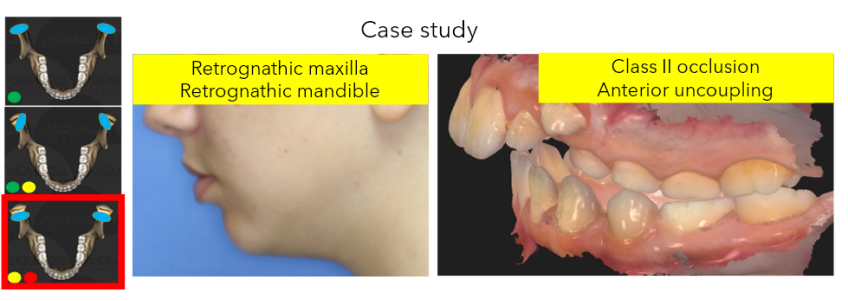

Clicking joints in growing patients increases the likelihood that the disk is not covering the condyle during the growing years. In this scenario, there is an increased likelihood of decreased growth compared to normal growth. Nebbe wrote in 1997 about “the findings of the current study tend to support the argument that internal derangement may be associated with altered craniofacial morphology in an adolescent sample. This pilot study shows reductions in total posterior facial height development and ramus height and a compensatory adaptation in the maxillary dentoalveolar region with reduced vertical development of the maxillary first molar region.” The retrognathic mandible and maxilla increase the likelihood of having structurally altered TMJs at the lateral and medial poles.

The Class II occlusion in a growing patient increases the likelihood the disc is not covering the condyle. Many patients like this are sent to the orthodontist and they expect a perfect result. The Class II occlusion is usually due to a loss of joint dimension in the TMJ. The loss of TMJ dimension is almost universally due to the disk not covering the condyle.

Confirming the diagnosis by MRI

Based on the information we gather during the initial consultation and the clinical exam, we must make a tentative TMJ diagnosis. After collecting the information in this case, it appears the tentative TMJ diagnosis is SA/LP/MP TMJs. These types of jaw joints have an increased likelihood of presenting with either pain, a Class II occlusion, or, in this challenging case, both pain and malocclusion.

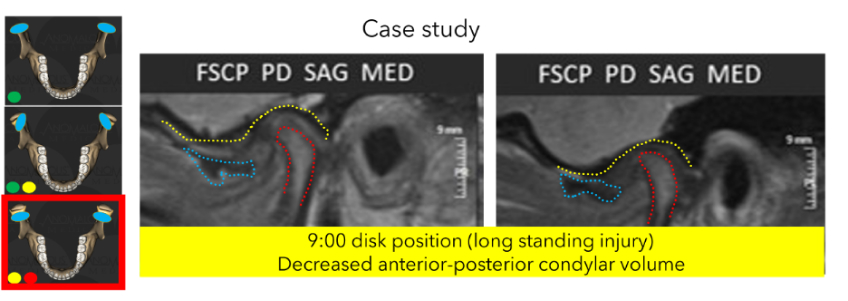

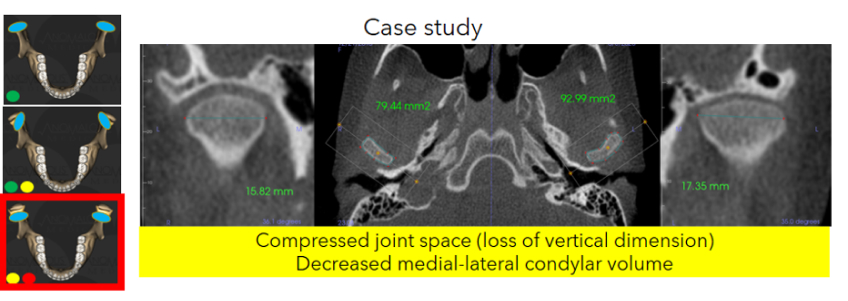

The MRI confirms the structurally altered TMJ at the medial pole.

In examining this clinical case and reviewing imaging findings, several insights into TMJ health in growing patients emerge. The patient’s presentation with Class II occlusions, anterior uncoupling, and retrognathic maxilla and mandible underscores the prevalence of TMJ structural issues in younger populations. Literature supports that such TMJ abnormalities are more common than previously recognized, potentially impacting craniofacial development. Diagnostic MRI confirmed decreased condylar volume and abnormal disk positioning, validating suspicions of structural alterations in the TMJ at the medial pole. These findings underscore the importance of thorough TMJ evaluation in orthodontic planning, facilitating the optimization of treatment outcomes and minimizing long-term joint complications in growing patients.

References

- Nebbe, B., Major, P. W., Prasad, N. G., Grace, M., & Kamelchuk, L. S. (1997). TMJ internal derangement and adolescent craniofacial morphology: a pilot study. The Angle Orthodontist, 67(6), 407-414.

- Cortés, D., Exss, E., Marholz, C., Millas, R., & Moncada, G. (2011). Association between disk position and degenerative bone changes of the temporomandibular joints: an imaging study in subjects with TMD. CRANIO®, 29(2), 117-126.

- Schellhas, K. P., Pollei, S. R., & Wilkes, C. H. (1993). Pediatric internal derangements of the temporomandibular joint: effect on facial development. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 104(1), 51-59.

SPEAR campus

Hands-On Learning in Spear Workshops

With enhanced safety and sterilization measures in place, the Spear Campus is now reopened for hands-on clinical CE workshops. As you consider a trip to Scottsdale, please visit our campus page for more details, including information on instructors, CE curricula and dates that will work for your schedule.

By: Jim McKee

Date: July 23, 2024

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts