Planning the Class IV: Workhorse of Cosmetic Dentistry, Part 2

Part two of a series of articles exploring the esthetics of a Class IV direct composite restoration.

In part one of this series, we discussed how a clear understanding of the Class IV direct restoration is the gateway to all knowledge of direct bonding in the anterior dentition. We also discussed the case of a female patient in her early twenties with esthetic complaints and a diagnosis of altered passive eruption (APE) and tooth surface loss (TSL).

In this article, we will discuss the ideal tooth preparation stages before bonding. To illustrate, we will discuss the case of a 21-year-old male who presented with TSL related to nocturnal bruxism. His complaints were mainly esthetic regarding the lateral incisors and canines (Fig. 1).

Due to the patient’s age, a decision was made to treat him with a purely additive approach with direct composite resin of the upper and lower anterior sextants alongside an occlusal equilibration.

The figures below highlight the new occlusal scheme in protrusive (Fig. 5), which moves from canine guidance to crossover (Figs. 6 and 7).

Small Class IV restorations, like the case illustrated above, cause practitioners the most issues with repeated debonds. Before layering the Class IV restoration, this article will consider a protocol for predictable bonding to tooth structure (enamel and dentin). This protocol is standard for all bonding and can be employed for any anterior direct procedure.

Particle Abrasion

Particle abrasion — sometimes known as air abrasion — was first developed in dentistry in the 1940s by Dr. Robert Black. In the United States, Dr. J. Tim Rainey further improved it and combined it with adhesive technology. Dr. Rainey could be considered the father of modern microdentistry.

Particle abrasion is “the process of tooth substrate removal utilizing the kinetic energy from particles entered in a high velocity stream of gas +/- fluid.”1 The gas is usually compressed air from the delivery cart and is sometimes augmented with water or a water/alcohol mix.

I prefer the addition of an alcohol/water mix —also called hydro-abrasion — since fewer particles are required for the abrasion. Importantly, the process is also cleaner with less dust contamination of the surrounding air.

Reduced dust is healthier for the operator and less damaging to surrounding equipment such as handpieces, microscopes and camera gear. Examples of available hydro-abrasion units include Velopex Aquacare and PrepStart H2O.

The particles commonly employed for restorative dentistry are aluminum oxide, glycine and SYLC. Aluminum oxide is most used since it offers sharp, irregular particles of the required hardness at a low cost.

Remember

Kinetic energy = ½ MV2

M = mass, V = velocity

It therefore follows that increased cutting efficiency will be gained by:

- Greater particle mass

- Increased velocity of the particles resulting from either higher air pressure, narrower bore of delivery tip or the tip being closer to the tooth structure1

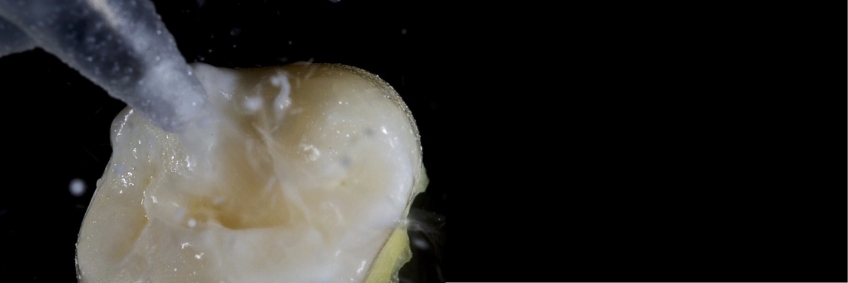

I use 27-micron alumina at a pressure of around 2-3 bar. When using the unit, the tip is held close to the tooth but continually in motion — dwelling in one area increases the degree of cutting. The motion used is a crisscross, checkerboard-shaped movement.

Particle abrasion improves bond strengths and restoration longevity as a result of:

- Removal of biofilm such as plaque, calculus, and staining<

- Removal of old composite bonding

- Removal of the aprismatic layer of enamel

What Is the Aprismatic Layer?

All enamel surface layers are comprised of amorphous, highly fluoridated, remineralised enamel around 10-30 microns in thickness — this is the aprismatic layer.

When we eat sugar, our oral biofilm creates acids. This acid attacks the tooth surface, causing the so-called “carious challenge.” This results in the loss of hydroxyapatite from the surface of our enamel (demineralization). Fortunately, most of us have fluoride in our diet or in toothpastes, mouthwashes, and floss. The fluoride demineralizes the enamel, creating the aprismatic layer. The aprismatic layer lacks a prism structure and is, therefore, more resistant to future acid attack.

As restorative dentists, we aim to etch teeth with 35–37% phosphoric acid to bond to them, but the aprismatic layer makes this less effective. Additionally, the aprismatic layer is only loosely adherent to the underlying main body of enamel. This means that when we bond to aprismatic enamel, we can achieve weak bonds.

However, heat is generated when we begin to polish the restoration because of the friction between the polishing rubber/disc and the tooth/restoration surfaces. Each component of the tooth-restoration interface, including enamel, dentin, bonding agent, and composite resin, has a different coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE). This means they expand and contract at different rates when heated.

As a result of the CTE mismatch, the weakest link in the system often breaks down during the polishing process. This is commonly the link between the aprismatic enamel and the underlying enamel. On a clinical level, a white line may appear during the polishing process that was not present before polishing. Particle abrasion reduces this risk.

Sharp cavosurface angles create stress risers. A stress riser is an area of high stress concentration which may result in adhesive bond breakdown. Particle abrasion creates rounded cavosurface angles.

Rounding of the margins is caused by “fanning” of the adhesive particles as the exit the orifice of the instrument tip (Fig. 8). However, abrasion provided by the peripheral portion of the stream is less efficient due to the lower velocity and concentration of alumina particles. This results in the rounding of all internal line angles.

This effect is minimized when the tip is sited less than 1.0 mm from the tooth, where fanning is negligible. Therefore, for any preparation requiring a rounded cavosurface margin, the instrument tip should be placed 2.0 mm from the tooth surface. If a butt joint is required, a distance of 0.5 mm should be employed.2

There is a wealth of research, both in vitro and in vivo, that demonstrates an increase in bond strengths to enamel after particle abrasion.3 4 5 6 However, the effects on dentin bonding are more controversial. Particle abrasion reduces smear layer thickness in comparison to bur-prepared dentin. Since they contain weaker acids and are less able to penetrate the smear layer, the performance of self-etching bonding agents may be improved.7 This effect is not seen in etch and rinse dentin bonding agents.

In contrast, particle abrasion may result in splitting of the collagen fibers on the dentin surface, reducing the quality of the hybrid layer.8 Anecdotally, I have used lower mass particles at low pressures for 15 years with no discernible adverse effects.

It is prudent to protect the adjacent teeth when carrying out particle abrasion and bonding procedures to avoid iatrogenic damage and linking the teeth together. I tend to employ Tofflemire bands without the matrix bands interproximal (Fig. 9). Note the matte appearance of the enamel surface following hydro-abrasion.

Tooth Preparation With Burs

Following particle abrasion, the tooth is prepared on the facial and interproximal surfaces.

Facial

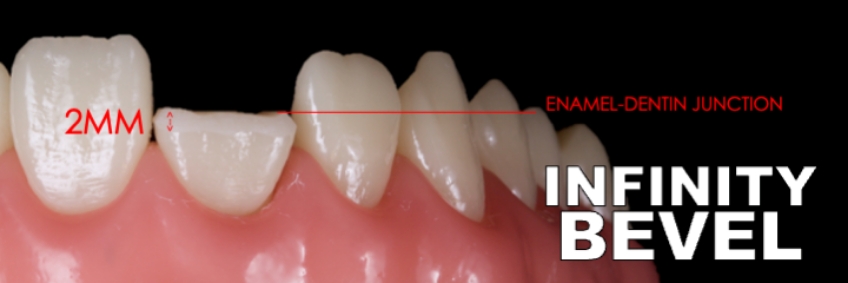

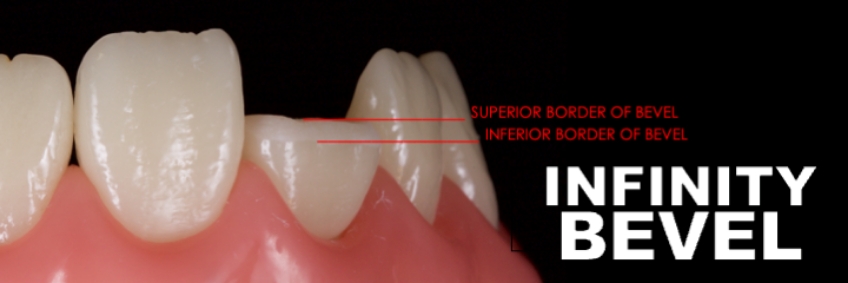

A coarse or medium diamond flame-shaped bur (863) is used to create a 2.0 mm long bevel extending from the enamel-dentin junction superiorly to a knife edge within the enamel inferiorly (Fig. 10). The bevel has an inferior and superior border (Fig. 11) — this is discussed in more detail in the final article in this series.

Key advantages of the bevel:

- The bevel provides an increased surface area for bonding improving retention.

- From an esthetic standpoint, when layering over the bevel there is a greater capacity to create an invisible margin in comparison to a butt joint.

A coarse/medium diamond has the advantage of efficiency when creating the bevel. However, the large particles on the bur tend to cause microfractures of the enamel at the cavosurface.

Remember that composite resin contracts as it polymerizes (polymerization shrinkage) and sets up stresses. These stresses may cause breakdown of the weakest link — often between the fractured enamel prisms and the main body of the enamel. Consequently, fractured enamel prisms pull away with the contracting composite. This is called the “enamel peel concept” and is a cause of white lines at the restoration margin.

Restorative dentists can avoid this problem by finishing the bevel at extremely low speed (3000 RPM) and water spray with a flame carbide finishing bur — this will reduce the number of fractured prisms. Practitioners should avoid polishing with a silicone point because silicone debris may remain — this results in decreased bond strengths.

Interproximal

The mesial and distal interproximal surfaces are finished with a metal finishing strip. These are available from Brassler, GC, and Cosmedent, amongst others. This will remove staining, old composite resin, biofilm, and the aprismatic layer. This step will mean the restoration is less likely to stain interproximally in the mid-term. The transition from incisal edge to interproximal is rounded off with a medium disc (e.g., Soflex, 3M) to remove sharp line angles and reduce stress.

Palatal

The palatal margin is finished as a simple butt joint. Correctly finished MID and MI preparations are seen clinically (Fig. 12). Explore bonding and layering the Class IV Restoration in the next and final article in this series.

References

- Bryant, C. L. (1999). The role of air abrasion in preventing and treating early pit and fissure caries. Journal (Canadian Dental Association), 65(10), 566-569.

- Nayak, U. S. D., Ignatius, G., Shenoy, A., & Nayak, S. D. (2013). Minimal intervention dentistry: air abrasion. Heal Talk, 5(4), 12-13.

- Laurell, K. (1993). Kinetic cavity preparation effects on bonding to enamel and dentin. The Journal of Dental Research, 273.

- Keen, D. S. (1994). Airadbrasive “etching”: composite hbond strengths. The Journal of Dental Research, 73, 131.

- Berry III, E. A., & Ward, M. (1995). Bond strength of resin composite to air-abraded enamel. Quintessence International, 26(8).

- Yazici, A. R., Kiremitçi, A., & Dayangaç, B. (2006). A two-year clinical evaluation of pit and fissure sealants placed with and without air abrasion pretreatment in teenagers. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 137(10), 1401-1405.

- Laurell, K. A., & Hess, J. A. (1995). Scanning electron micrographic effects of air-abrasion cavity preparation on human enamel and dentin. Quintessence International, 26(2).

- Nikaido, T., Yamada, T., Koh, Y., Burrow, M. F., & Takatsu, T. (1995). Effect of air-powder polishing on adhesion of bonding systems to tooth substrates. Dental Materials, 11(4), 258-264.

FOUNDATIONS MEMBERSHIP

New Dentist?

This Program Is Just for You!

Spear’s Foundations membership is specifically for dentists in their first 0–5 years of practice. For less than you charge for one crown, get a full year of training that applies to your daily work, including guidance from trusted faculty and support from a community of peers — all for only $599 a year.

By: Jason Smithson

Date: July 30, 2021

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts