Ultra-Conservative Management of the Discolored Tooth

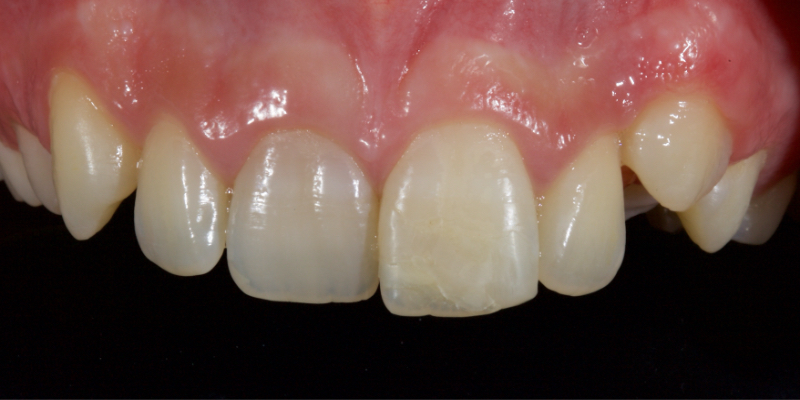

Historically, discolored anterior teeth were treated with indirect ceramic restorations, such as crowns or veneers. This can be illustrated in the case shown in Figure 1, where the discolored left central incisor (2.1), along with two other incisors, was treated with lithium disilicate ceramic veneers (Fig. 2). More recently, direct composite materials that incorporate specialized “opaquers” have also been utilized for treatment.

These strategies offer esthetic and predictable outcomes. However, this is often at the expense of tooth structure. Iatrogenic loss of tooth structure can result in premature extraction due to catastrophic fracture. This is of particular concern with non-vital teeth, which are already structurally compromised by endodontic procedures.

This article explores a more modern, minimally invasive approach to discolored non-vital teeth using the “modified walking bleach” approach. Figure 3 (before treatment) and Figure 4 (after treatment) show an example of this highly conservative approach.

An Overview of Tooth Discoloration

Compounds known as “chromophores” discolor teeth. Chromophores are chemical groups capable of selective light absorption, resulting in the adverse discoloration of dentin and enamel. Tooth discoloration is caused by a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic chromophores, sometimes in addition to aging effects.

Intrinsic Discoloration

This is caused by incorporating chromogenic material into dentin and/or enamel either during odontogenesis or after eruption.

Pre-eruptive discoloration may be the result of exposure to high levels of fluoride (fluorosis); tetracycline administration, inherited developmental disorders (for example, erythroblastosis foetalis, porphyria, thalassemia, or sickle cell crises), or trauma to the developing tooth. See the brown and white discoloration of the upper right central incisor after trauma in Figure 5.

Post-eruptive discoloration is usually seen after pulp necrosis, intrapulpal hemorrhage, pulp remnants remaining after endodontic therapy, or due to iatrogenic factors (such as silver amalgam or “Russian Red” endodontic therapies).

In Figure 6, the patient has calcific metamorphosis of the upper right central incisor.

Calcific metamorphosis is “a pulpal response to trauma characterized by rapid deposition of hard tissue within the canal space (AAE, 2012).” It is seen clinically as a red/brown discoloration of the tooth and radiographically as reduced canal space compared to neighboring teeth.

In my experience, teeth affected with calcific metamorphosis tend to respond unpredictably to non-vital bleaching and often suffer relapse. These teeth are usually best restored with ceramic restorations.

Aging causes an increase in chroma and decrease in value of the tooth for two reasons:

- The enamel wears over time and becomes thinner; therefore, the dentin is more visible, increasing the tooth’s chroma.

- Within the dentin, there is secondary and tertiary dentin deposition within the dentinal tubules over time. This means that in younger patients, the dentin is more heterogeneous in terms of the mix of inorganic/organic matter and water within the dentin. As we age, the pulp recedes and the dentinal tubules become filled with secondary and tertiary dentin. In the older tooth, the dentin is therefore more homogeneous. More homogeneous dentin scatters light less, and light penetration of the tooth is increased; as a result, the tooth becomes more translucent as we age. The net result is a drop in value with aging.

Extrinsic Discoloration

This is seen as reversible discoloration on the tooth’s surface, commonly caused by coffee, tea, red wine, and tobacco (Hattab et al., 1999). It is usually simple to remove with a scale and polish. This article focuses on bleaching the discolored non-vital, endodontically treated tooth, usually with intrinsic discoloration.

Approaches to Non-Vital Bleaching

Non-vital bleaching was initially described in 1864 by Truman (Truman, 1864). Latterly, one of four main techniques is employed:

- Thermocatalytic Technique

This approach places 30-35% hydrogen peroxide into the pulp chamber. Heat is applied either with a heated metal instrument or a commercial heat applicator (e.g., Touch’n Heat, System B). The heat is thought to increase the bleaching properties of the hydrogen peroxide (Howell, 1980). This technique has fallen out of vogue since the combination of hydrogen peroxide, heat, and lack of a coronal barrier seal is known to increase the incidence of external cervical resorption (Frank, 1981). - In-Office Technique

Here, the tooth is isolated with a rubber dam, and the whitening gels are applied either directly or contained within a bleaching tray. The treatment is carried out in the dental office. Typically, high concentrations of carbamide or hydrogen peroxide are used. The endodontic access may be open or closed. This technique has good efficacy. However, one must be mindful of the chair time this consumes and the consequent financial cost to the patient. - Walking Bleach Technique

Marsh first described this approach, and it was later published by Salvas (Salvas, 1938). A mixture of sodium perborate and water or hydrogen peroxide is sealed into the pulp chamber and left for several days; it is then replenished to bleach the tooth. It is a highly successful approach (Nutting and Poe, 1967). However, one should consider that multiple visits would be required, in addition to the fact that the access must be opened multiple times. Remember that every time we access a tooth, even with meticulous care, we remove more dentine and enamel. This may have implications for structurally compromised teeth. - Then there is the Modified Walking Bleach Technique

Also known as the Inside/Outside Open Technique, this approach was first described by Settembrini et al, 1997, and later by Liebenberg et al, 1997.

In this technique the endodontic access remains open with the endodontic seal being protected with a Coronal Barrier Seal (see below). The patient directly applies the bleaching agent into the access cavity and also to a bleaching tray, which is fitted over the teeth. The procedure is repeated every 2-3 hours and the patient is reviewed at 2-3 days.

In my experience, this approach is extremely effective at minimal cost to tooth structure and the patient’s pocketbook. Further, the modified walking bleach approach is the fastest method (Lise et al., 2018) with the least chair time, which tends to be more acceptable to both clinician and patient.

In this example of the Modified Walking Bleach Approach, the patient presented with a discolored upper right central incisor (1.1, Fig. 7). The old restoration was removed, an endodontic retreatment was carried out, and a coronal barrier seal was placed (Fig. 8). The access cavity was left open (Fig. 9).

The patient carried out the modified walking bleach technique with a nightguard for 48 hours (Fig. 10). I prefer to mark the night guard with a Sharpie marker to enable the patient to visualize the correct tooth to treat. The patient returned for review after successful whitening (Fig. 11).

Why Carbamide Peroxide?

The active ingredient in dental bleaching is hydrogen peroxide (HP). HP acts as a strong oxidizing agent by forming free radicals, reactive oxygen molecules, and hydrogen peroxide anions (Gregus and Klaassen, 1995).

These reactive molecules attack the long-chained, dark-colored chromophore molecules, breaking down the conjugated double bonds and splitting them into smaller, less colored, and more diffusible molecules, such as alcohols, ketones, and terminal carboxylic acids. To summarize, the chromophores are “chopped up.”

HP may be applied in one of three ways:

- Hydrogen peroxide

- Sodium perborate (SP)

- Carbamide peroxide (CP)

I prefer CP. Why? The European Commission has banned SP, and it’s no longer in routine use in Europe.

CP is also known as hydrogen peroxide-urea. This breaks down to produce urea, which breaks down to Ammonia (Budavari et al, 1989). This results in an increase in pH. In a basic solution, less activation energy is required for HP to produce free radicals, and the reaction rate is therefore faster (Sun, 2000)

There appear to be no reported cases of External Cervical Resorption (ECR) involving 10% CP in the literature. Further, high concentrations of HP may result in chemical burns of the oral mucosa and soft tissues of the face or eyes. Greenwall-Cohen (2017) described the beneficial effect of 10% CP on both oral hygiene and the oral mucosa.

External Cervical Resorption (ECR)

Tooth resorption is defined as the loss of dental hard tissue (cementum and dentin) as a result of the action of odontoclasts. Root resorption may be internal (from the root canal) or external (on the surface of the root). External root resorption is further classified as:

- Surface resorption

- External inflammatory resorption

- External replacement resorption

- External cervical resorption

- Transient apical breakdown

It’s beyond the scope of this article to explore all the classifications. However, ECR (also known as invasive cervical resorption) is a relatively uncommon, insidious, and often aggressive form of external tooth resorption. It occurs on the root at the level of the connective tissue attachment of the periodontium (Tronstad, 1980).

It was first described by Mueller and Rony (1930) and is seen as highly vascular pink tissue replacing the resorbed hard tissue.

Harrington’s Group in the 1970s (Harrington et al, 1979) first documented ECR as a side effect of non-vital bleaching.

Although the etiology is unknown, the process is proven to be exacerbated by intra-coronal bleaching (Goon et al., 1986).

Postulated theories include:

- Bleaching agent reaches periodontium via dentinal tubules and initiates an inflammatory reaction (Cvek et al, 1985).

- Peroxide travels through dentinal tubules and denatures dentin, which becomes immunologically different and is attacked as a foreign body (Lado et al, 1983).

In either case, the problem is that the bleaching products travel via the dentinal tubules to the root surface. The solution is the coronal barrier seal.

The Coronal Barrier Seal

A coronal barrier seal is required to prevent the apical progress of bleaching agents/their derivatives from the pulp chamber to the root surface via the dentinal tubules (Hansen-Bayless and Davis, 1992). An ideal coronal barrier seal is demonstrated in this case, in which a young patient presented with a discolored upper right central incisor (1.1) that had previously suffered an Ellis Class III fracture (Fig. 12).

The existing palatal restoration and some pulp horn remnants were removed from an operating microscope under enhanced vision. (Fig. 13)

A RMGIC 3.0 mm coronal barrier seal was placed (Fig. 14). The 1.1 was bleached over three days (Fig. 15). The existing restoration was removed under local anesthesia (Fig. 16), and a definitive direct resin restoration was placed (Fig. 17).

Where Should the Barrier Be Located?

Historically, the barrier was placed at the position of the CEJ (Steiner and West, 1994). The issue is that the root is not bleached, which may produce an esthetic defect if there is recession or a thin biotype.

It should be remembered that the dentinal tubules run apically from pulp chamber to periodontium.

The ideal barrier will be 1.0 mm above the osseous crest and 2.0 mm below the osseous crest, for a total of 3.0 mm in section. This allows bleaching of the root without risk of ECR.

The position is determined by bone sounding under local anesthesia, which is done mid-buccally, mesially, and distally (Kois, 1994, 1996).

What Shape Should the Barrier Take?

The osseous crest’s architecture is typically parabolic, being more coronal interproximal and more apical at the mid-buccal. The soft tissues of the gingivae follow the bone.

The exceptions are some cases with bone loss secondary to periodontitis, where the osseous crest may be flat. The coronal barrier seal should closely follow the bone architecture.

A common error is to create a flat barrier, which introduces two problems: It is too low interproximally, and there is a risk of ECR. The coronal barrier seal is too high at the mid-buccal, and the tooth fails to bleach there, resulting in an aesthetic issue.

What Is the Ideal Material?

The most ideal materials are resin-modified glass ionomer cements and cavit: the authors preference is RMGIC in white shade due to its ease of placement and high visibility if a later endodontic retreatment is required.

Bleaching Trays

I use a horseshoe-shaped tray, which extends around 2.0 mm onto the attached gingivae with a scalloped margin design. Non-scalloped designs are also acceptable. The material is 0.035 in section, semi-rigid, thermoplastic and vacuum formed.

Effect on Bond Strengths

Cvitko et al. (1991) demonstrated that after bleaching, a two-week reduction in bond strengths of composite resin of between 25 and 50% could be noted.

This is due to residual HP breakdown products remaining in the dentinal tubules. Remember, the polymerization of composite resin is oxygen-inhibited. For this reason, glass ionomer is used as a temporary restoration, and final restoration with adhesive resin-based restorations is deferred for a minimum of two weeks after bleaching is completed (Omrani et al., 2016).

Protocol

- The discolored tooth is assessed. Any teeth that exhibit symptoms or clinical/radiographic signs of endodontic failure should be endodontically retreated.

- Any excess composite resin is removed from the facial surface of the tooth. Composite resin creates a seal, which reduces the efficacy of the bleaching process.

- Impressions (digital or analogue) are taken for bleaching trays.

- The palatal seal is completely removed to 2.0 mm below the osseous crest. This is measured using the incisal edge as a reference point and compared with the bone-sounding measurements. A Williams periodontal probe is used.

- The RMGIC coronal barrier seal is placed. The position is verified with a periapical radiograph. This is important for both clinical and medico-legal reasons.

- The placement of CP and the fitting of bleaching trays are demonstrated to the patient.

- The patient is then discharged with instructions to change the CP every two hours. At each change, the tray should be cleaned under running water with a toothbrush, and the access cavity should be irrigated with water from a 5-ml Monoject syringe.

- The patient is recalled after three days. If bleaching is incomplete, the patient must continue for two days. This is very unusual if the patient has closely complied with instructions.

- The access cavity is sealed with Teflon tape (plumber’s tape) and RMGIC, and the patient is discharged with a warning to avoid hard foods.

- After a minimum of two weeks, the patient is recalled and the tooth is definitively restored with a direct resin or ceramic restoration.

Conclusion and Consideration of Ultra-Conservative Approach

The following case illustrates the ultra-conservative approach in a teenage patient who presented with non-vital upper central incisors, a discolored upper right central incisor (1.1) and a fractured upper left central incisor (2.1) following a skiing accident (Fig. 18).

Figure 23 shows the endodontic treatment, the coronal barrier seal, and the final palatal composite restoration.

Combined with direct composite, the modified walking bleach technique offers a predictable, rapid, cost-efficient, and highly conservative alternative to indirect restorations in managing discolored non-vital teeth.

References

- American Association of Endodontists. (2003). Glossary of Endodontic Terms. American Association of Endodontists.

- Hattab, F. N., Qudeimat, M. A., & AL‐RIMAWI, H. S. (1999). Dental discoloration: an overview. Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry, 11(6), 291-310.

- Truman, J. (1864). Bleaching of non-vital discoloured anterior teeth. Dental Times, 1(1), 69-72.

- Howell, R. A. (1980). Bleaching discoloured root-filled teeth. British Dental Journal, 148(6), 159-162.

- Frank, A. L. (1981). External-internal progressive resorption and its nonsurgical correction. Journal of Endodontics, 7(10), 473-476.

- Salvas, J. C. (1938). Perborate as a bleaching agent. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 25, 324-326.

- Nutting, E. B., & Poe, G. S. (1967). Chemical bleaching of discolored endodontically treated teeth. Dental Clinics of North America, 11(3), 655-662.

- Settembrini, L., Gultz, J., Kaim, J., & Scherer, W. (1997). A technique for bleaching nonvital teeth: inside/outside bleaching. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 128(9), 1283-1284.

- Liebenberg, W. H. (1997). Intracoronal lightening of discolored pulpless teeth: a modified walking bleach technique. Quintessence International, 28(12).

- Lise, D. P., Siedschlag, G., Bernardon, J. K., & Baratieri, L. N. (2018). Randomized clinical trial of 2 nonvital tooth bleaching techniques: A 1-year follow-up. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 119(1), 53-59.

- Gregus, Z. (2008). Mechanisms of toxicity. Casarett and Doull’s Toxicology: The Basic Science of Poisons, 45-106.

- O’Neil, M. J. (2013). The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals. RSc Publishing.

- Sun, G. (2000). The role of lasers in cosmetic dentistry. Dental Clinics, 44(4), 831-850.

- Greenwall-Cohen, J., & Greenwall, L. (2017). Carbamide peroxide and its use in oral hygiene and health. Dental Update, 44(9), 863-869.

- Mueller, E., & Rony, H. R. (1930). Laboratory studies of an unusual case of resorption. The Journal of the American Dental Association (1922), 17(2), 326-334.

- Tronstad, L. (1988). Root resorption—etiology, terminology and clinical manifestations. Dental Traumatology, 4(6), 241-252.

SPEAR ONLINE

Team Training to Empower Every Role

Spear Online encourages team alignment with role-specific CE video lessons and other resources that enable office managers, assistants and everyone in your practice to understand how they contribute to better patient care.

By: Jason Smithson

Date: March 26, 2021

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts