Managing Over-Eruption Following Tooth Wear

Treatment-planning patients who’ve had tooth eruption after tooth wear and a subsequent lack of room for restoration presents a challenging and commonly encountered problem in practice. This article focuses on what can be a very confusing problem for clinicians: the presence of isolated wear on segments of teeth, rather than generalized wear on all the teeth.

Several different terms are used to describe this process in the literature, including compensatory eruption, supereruption, supraeruption, hypereruption, and secondary eruption, just to name a few. For the purposes of this article, I’ll simply use the term “eruption.” The literature also describes two types of continued eruption in humans after the loss of an opposing tooth, or to maintain occlusal contact following wear.

(Click here to learn more about the common causes of tooth wear.)

The most common type of eruption after tooth wear can be described as dentoalveolar extrusion, where the tooth, gingiva, and alveolus all move coronally, increasing the zone of attached gingiva in the process, with minimal to no change in the CEJ-to-bone relationship. The second type can be called continued active eruption, where the tooth erupts but the gingiva and bone do not, exposing the CEJ and root surface in the process. This second type occurs less frequently, and is much easier to treat because the gingiva, papilla, and bone remain in the correct position.

Some fundamental concepts can be helpful in understanding the process that triggered the eruption after tooth wear. If a tooth wears in areas where it occludes with the opposing tooth, regardless of the etiology for the wear, attrition, erosion, or abrasion, there are a limited number of possibilities that can occur. Either the tooth or its opposing tooth or teeth will erupt to maintain the occlusion, not erupt and develop an open bite, or if minimal or no eruption has occurred, it is possible to maintain the occlusal contact if the patient’s vertical dimension decreases.

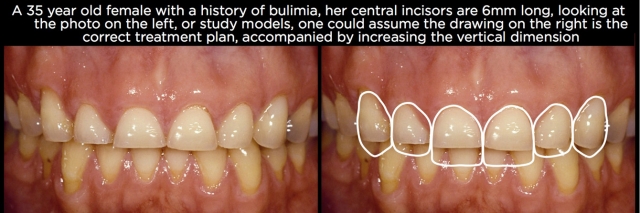

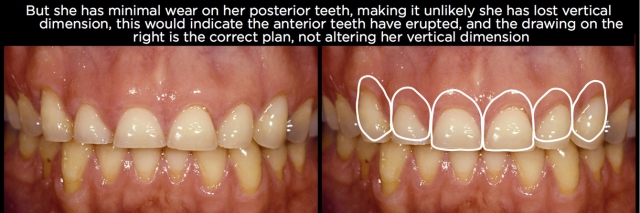

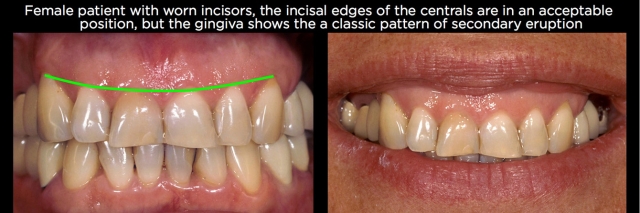

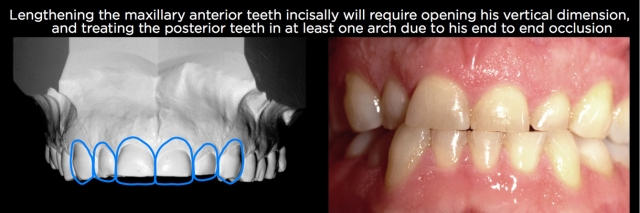

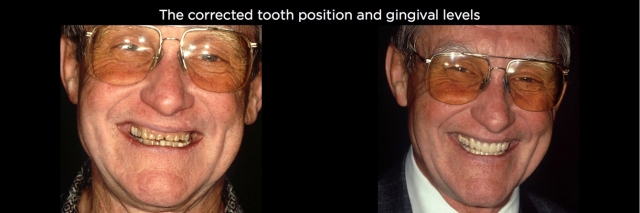

An additional concept concerning vertical dimension can aid in understanding the process even further. For a patient to have lost vertical dimension, there has to have been changes to every pair of occluding teeth. In other words, if you have wear only on the maxillary anterior teeth, and they are in occlusion, and there’s no wear on any posterior teeth (not uncommon in bulimia and certain patterns of bruxism or parafunction), it’s likely there has been minimal to no change in occlusal vertical dimension, but instead eruption of the anterior teeth to maintain the occlusal contact. (Fig. 1)

This is a critical point, because the most common response to seeing anterior wear is to assume that it will be necessary to increase the vertical dimension to create room for a restoration and to correct the length of the teeth. If the wear is isolated to the anterior teeth, correcting the eruption will create the space needed for the restoration, and will not require any alterations to the posterior teeth.

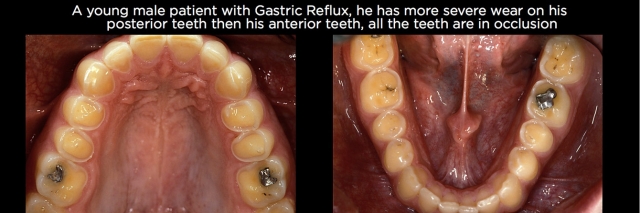

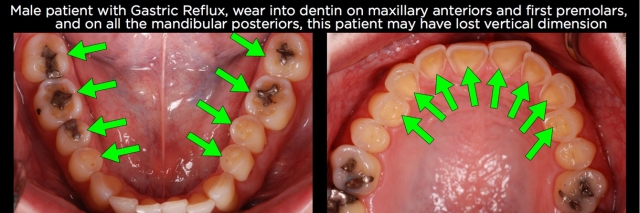

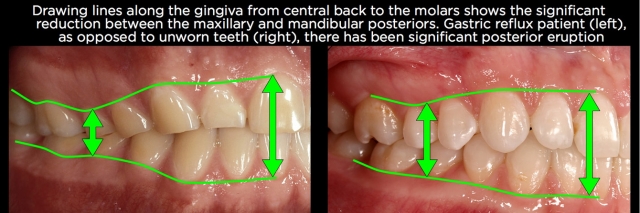

The same holds true for wear on the posterior teeth. Using gastric reflux as an example, there are often times that the posterior teeth have significant wear on their occlusal surfaces while the anterior teeth may have minimal wear. It’s common to think that the patient has lost vertical dimension and will need the vertical dimension increased to create space for restoration of the posterior teeth. More commonly, the posterior teeth have erupted, especially if the anterior teeth have minimal wear, are not mobile and haven’t migrated facially (Fig. 2).

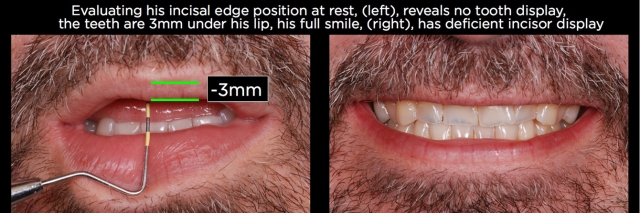

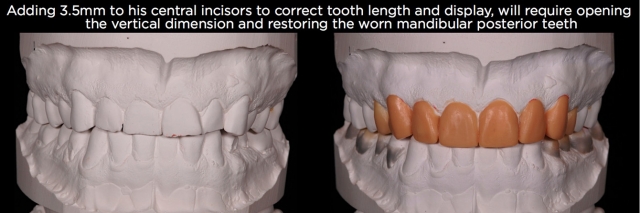

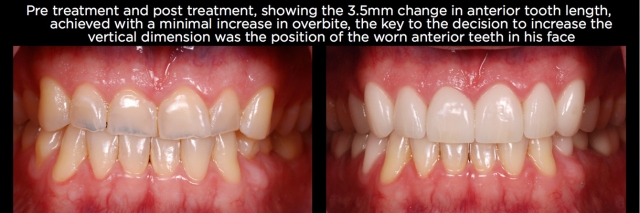

One of the reasons clinicians don’t see eruption has occurred is because they’re trying to treatment-plan from study models or intraoral photographs. When one looks at a set of study models or intraoral photos and sees 6-mm-long central incisors, it’s easy to assume they need to be lengthened 4.5 mm to produce a more normal 10.5-mm-long central. And it would be unusual to be able to lengthen the anterior teeth 4.5 mm in an incisal direction and not increase the vertical dimension; otherwise you would be increasing the overbite 4.5 mm (Figs. 3 and 4).

But what the models and intraoral photos don’t provide is a reference for the position of the teeth; they are only showing you the length of the teeth and the relationship of the anterior teeth to the posterior teeth in the arch, as well as the occlusal relationship between the arches. Necessary references for the position of the anterior teeth are the lips and face of the patient, most commonly done using photographs. It is the heart of the treatment planning system we teach, Facially Generated Treatment Planning.

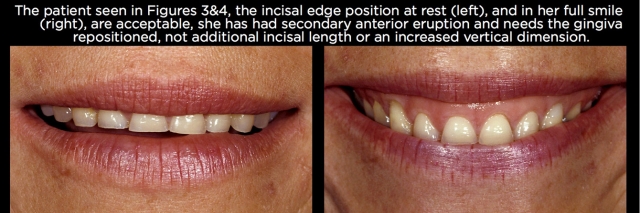

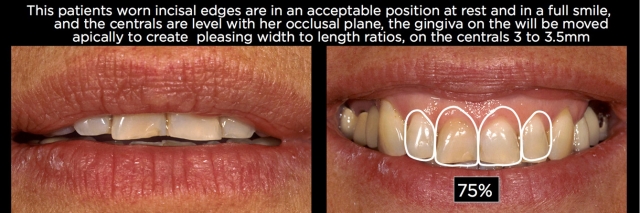

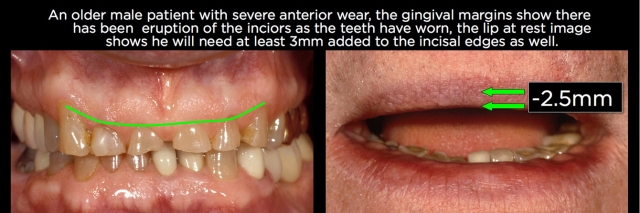

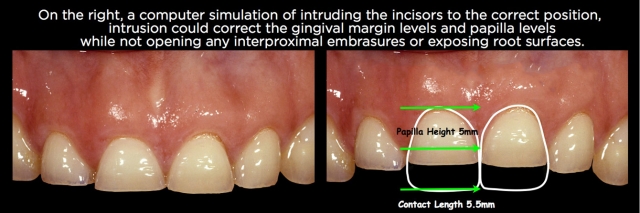

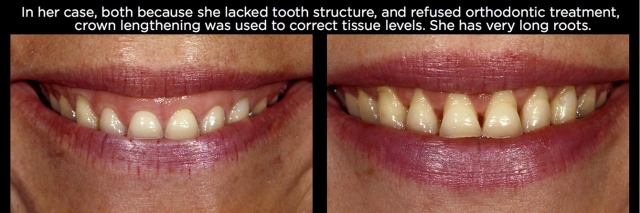

By using photographs of the patient’s lips at rest, along with full smile images, it becomes possible to determine whether the anterior teeth need to be lengthened 4.5 mm by adding to the incisal edges, or if the incisal edges are correct and correcting the tooth length would involve adjusting the anterior eruption, moving the gingiva apically 4.5 mm through crown lengthening or orthodontic intrusion (Fig. 5).

There are of course patients who do need the length of their worn anterior teeth lengthened by adding to the incisal edges and increasing their vertical dimension, but generally these patients will show wear on all their teeth, or at least on one of each occluding pair of teeth.10,11 An example may be erosive wear of the maxillary anterior teeth and mandibular posterior teeth, with minimal wear of the mandibular incisors and maxillary posteriors, as can be seen in certain cases from gastric reflux (Figs. 6–9).

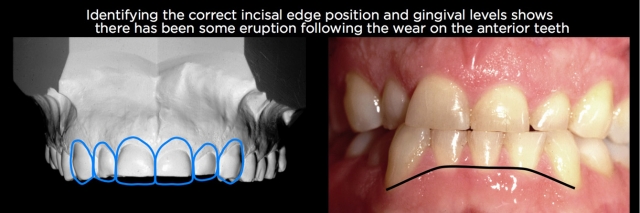

Along with evaluating the position of the teeth relative to the face using photographs, evaluation of the gingival margins of the teeth within the arch can be very helpful at identifying the presence of hypereruption. A common pattern seen in anterior eruption cases is when the gingival margins of the centrals are coronal to the laterals, which are coronal to the canines.

(Click here for a worn dentition case study.)

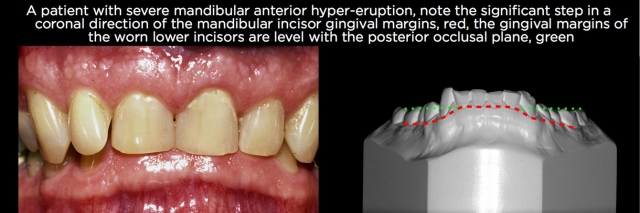

This eruption of the anterior teeth is easily seen if there has been no wear of the anterior teeth; the incisal edges of the centrals will be seen as stepped down relative to the posterior teeth. But in cases of eruption after anterior tooth wear, it is common to see the incisal edges of the erupted teeth level with the occlusal plane of the posteriors, or sometimes even apical to the occlusal plane of the posteriors, making the diagnosis of the eruption less obvious (Fig. 10).

The gingival margins can be very helpful to diagnose eruption after wear in the posterior as well. A useful way of looking at the gingival levels in the posterior — when there’s significant wear on the posterior teeth but not on the anteriors — is to examine lateral photographs of the patient in occlusion or study models in occlusion. Evaluate the distance from the gingival margins on the maxillary posteriors to mandibular posteriors, compared with the distance on the anterior teeth from maxillary to mandibular gingival levels. If posterior eruption has occurred, the reduction in distance between the gingival margins in the posterior is usually quite obvious (Figs. 11 and 12).

The gingival margins can also be useful for evaluating mandibular incisor eruption after tooth wear. Usually the step from canine to incisor gingival levels is exaggerated, with the incisor gingival levels being significantly more coronal (Fig. 13).

Treatment options

Once the diagnosis of eruption after tooth wear has been made, four options are available for treatment to correct the tooth position and tissue levels, creating room for restoration at the existing vertical dimension:

- Orthodontic intrusion followed by restoration.

- Periodontal crown lengthening followed by restoration.

- Extraction of the over-erupted teeth and prosthetic replacement.

- Orthognathic surgery to reposition the bone and teeth, followed by restoration.

Of these four, orthodontic intrusion and periodontal crown lengthening are the most common approaches to treating eruption after wear, assuming the patient’s teeth are restorable and the patient is willing to do the necessary treatment.

Increasing vertical dimension is also a method to create space to restore worn teeth. But only opening the vertical dimension doesn’t place the alveolar bone and gingiva back in their pre-erupted position, and therefore can have esthetic compromises unless combined with other treatment options such as crown lengthening or orthodontic intrusion to correct the bone and tissue position, along with opening vertical to create space.

The first step in choosing a treatment methodology is to identify the desired end point of treatment relative to tooth position, gingival levels, papilla levels and occlusion. This gives you the ability to compare the current position of the teeth and gingiva, and identify how much change is necessary to produce the desired final result. The greater the discrepancy between the current condition and desired end result, the more difficult achieving that result becomes, but it also helps in determining which methods of treatment might be the most successful.

There are several criteria that can be beneficial in making a decision among the four treatment options:

- Root length in bone and furcation location

- Tooth alignment within the arch and occlusal relationships

- Remaining tooth structure/length and condition

- Contact length/papilla height

- Periodontal status/existing bone levels

Root length and furcation location

Root length and furcation location are important in determining if periodontal crown lengthening is an acceptable option. Because the teeth will need a restoration whether crown lengthening or orthodontic intrusion is chosen, patients often prefer crown lengthening due to the shorter treatment times.

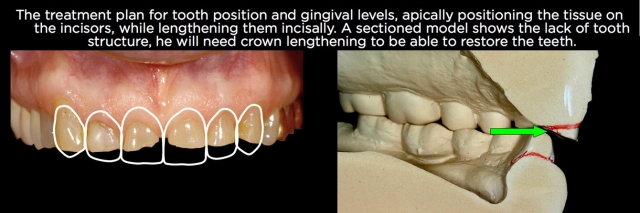

The first step in the process is to decide how many millimeters of facial, interproximal, and lingual crown lengthening would be necessary to correctly position the gingiva. This occurs after the desired incisal edge position of the anterior teeth has been identified and the correct position of the occlusal plane of the posterior teeth is defined.

For maxillary anterior teeth, the width-to-length ratio is then evaluated and the gingival margin position determined that produces a pleasing width-to-length ratio on the central incisors (generally 75%–80%). The canine gingival margin levels are placed at this same level, and the lateral gingival levels slightly coronal.

For posterior teeth, the width-to-length ratios are not critical, and gingival levels are generally based upon a pleasing flow with the canine gingival margins, or as necessary to provide adequate tooth structure to allow for restoration.

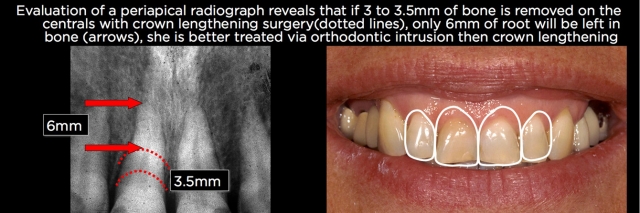

Once the amount of crown lengthening in millimeters is determined, it is now possible to use periapical radiographs to evaluate root length. Start by identifying the existing bone levels, then mark on the root where the bone would need to be moved to gain adequate crown length. From this position, it’s possible to measure to the apex of the root and see how much root would be left after crown-lengthening surgery.

Although clinicians frequently discuss maintaining a 1:1 crown-to-root ratio, experience shows that’s not necessary. My own rule is if 8–9 mm of root can be left in bone after surgery, the root is long enough. If less than 8 mm of root would be left in bone after crown lengthening, orthodontic intrusion is a better treatment option13 (Figs. 14 and 15).

In the posterior, particularly for molars, the location of the furcations can also be a significant limiting factor for crown lengthening, because it is desirable to not expose the furcations following surgery.

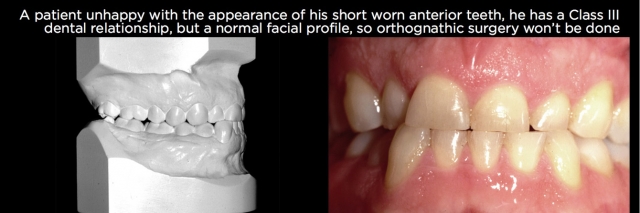

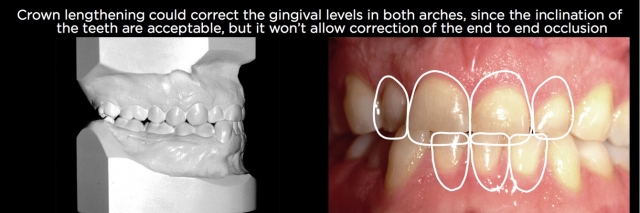

Tooth alignment/occlusal relationships

Just as adequate root length is a determinant of whether crown-lengthening surgery is an option, so is the facial lingual inclination of the overerupted teeth. Even though surgery can be performed on teeth that are significantly proclined or retroclined, the more apical the bone and gingiva are positioned, the more difficult the subsequent restorative process is and, in general, the use of orthodontics is a better choice to reposition the teeth and gingiva and correct the inclination than crown lengthening and trying to warp the restoration to the facial or lingual.

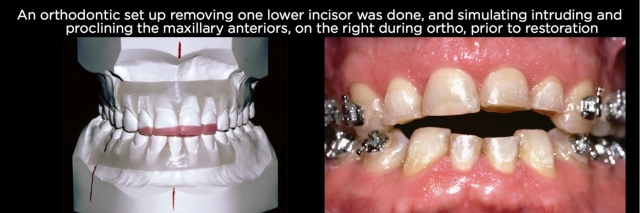

In addition, if there are occlusal relationship issues on the worn teeth, such as end-to-end occlusions or deep overbites, orthodontic correction of the eruption and correcting the occlusion is a better choice than crown lengthening and leaving the compromised occlusion (Figs. 16–21).

Remaining tooth structure/length and condition

These are critical for several reasons, especially to determine if the teeth are restorable. If the teeth have significant wear and are in poor condition with regard to their structural condition, then removal and replacement may be the best treatment option.

If the teeth are structurally sound but significantly worn, then it’s necessary to determine if there’s adequate tooth structure to restore. If there’s not, orthodontic intrusion is usually not a first choice because after the teeth are repositioned, there still won’t be adequate tooth structure to restore and it may be necessary after the intrusion to perform endodontics and place posts and cores on the teeth to allow them to be restored. (Figs. 22–25).

In cases where the amount of tooth structure is inadequate, crown lengthening is often the best choice to correct the eruption because it can expose more tooth structure to allow a predictable restoration, frequently eliminating the potential need for endodontics and posts and cores. If the tooth position is also not acceptable with regard to facial lingual inclination or occlusal relationships, a combination of crown lengthening and orthodontics might be necessary.

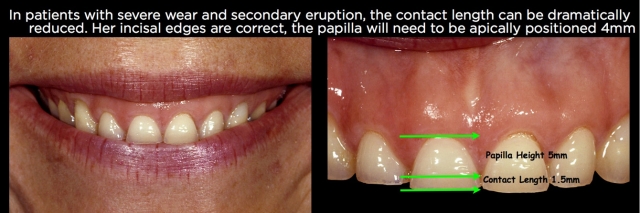

Contact length/papilla height

When teeth wear and erupt, it’s not just the gingival margin that moves in a coronal direction but also the papilla. In addition, the tooth wear reduces the length of the contact from incisal edge to tip of papilla. In well-aligned unworn central incisors, research shows us the length of the contact and the height of the papilla are essentially equal. For ease of treatment planning, I generally plan to position the papilla 5–6 mm from the desired incisal edge position and have a papilla that is 4.5 mm in height from gingival margin to the tip of the papilla.

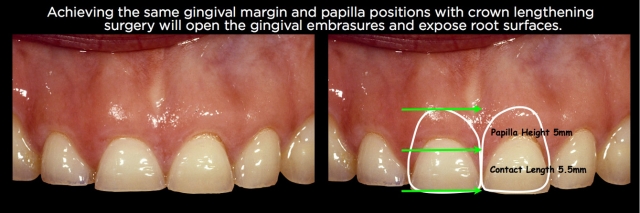

Achieving those goals using crown lengthening instead of orthodontic intrusion has some significant restorative ramifications that must be considered. Repositioning the papilla apically via surgery will always open up the gingival embrasures, necessitating the restorations go through the interproximal and have subgingival margins to close the open embrasure. In addition, repositioning the facial gingival margin 3 or 4 mm apically will almost always mean the restoration will have its margin on root surface rather than enamel (Figs. 26–30).

Using orthodontic intrusion to reposition the papilla and gingival margins apically eliminates the need for the restoration to go interproximally to close an open embrasure, and also allows the margins to potentially stay on enamel. Having said that, in cases of severe wear with inadequate tooth structure, surgery is preferable to expose enough tooth structure to restore, in spite of the additional compromises. But if adequate tooth structure to restore exists, intrusion can have some significant benefits.

Periodontal status/existing bone levels

If teeth have erupted after tooth wear but have some bone loss or had continued active eruption where the bone and gingiva did not erupt with the teeth, they become prime candidates to consider crown-lengthening surgery to correctly locate the papilla and gingival margins, because the amount of bone removal and tissue alteration may be minimal. In addition, if the teeth have erupted and the bone loss is severe, they become prime candidates for removal and replacement with implants.

One of the most significant challenges of replacing hypererupted teeth with implants is the amount of bone removal (ostectomy) necessary to correctly position the head of the implant fixture. If hypererupted teeth and inadequate bone are before implant placement, you now have to deal with essentially hypererupted implants, which can present significant restorative challenges.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article was to provide information on the eruptive process that typically occurs following tooth wear when it occurs on isolated segments of teeth in the mouth. The most common options for correction of the eruption have been reviewed, as well as the criteria that must be evaluated in making a final treatment decision. Hopefully this will provide insight into these challenging patients and how an interdisciplinary approach to treatment can help them.

References

- J Am Dent Assoc. 2010 Jun;141(6):647-55. Contemporary crown-lengthening therapy: a review. Hempton TJ1, Dominici JT.

- Int J Prosthodont. 2009 Jan-Feb;22(1):35-42. Prevalence of tooth wear in adults. Van’t Spijker A, Rodriguez JM, Kreulen CM, Bronkhorst EM, Bartlett DW, Creugers NH. Department of Oral Function and Prosthetic Dentistry, College of Dental Science, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

- British Dental Journal 197, 385–391 (2004). Eruptive tooth movement — the current state of knowledge. H L Craddock, C C Youngson.

- Compagnon D, Woda A. Supra-eruption of the unopposed maxillary molar. J Prosthet Dent 1991: 66: 29–34.

- Ainamo J, Talari. Eruptive Movements in Teeth in Human Adults. In: Poole D F G and Stack M V (eds). The Eruption and Occlusion of Teeth. London: Butterworth 1976; 97–107.

- Br Dent J. 1998 Mar 14;184(5):242-6. Factors affecting the lifespan of the human dentition in Britain prior to the seventeenth century. Kerr NW, Ringrose TJ.

- Ainamo A, Ainamo J. The width of attached gingiva on supraerupted teeth. J Periodontal Res 1978; 3: 194–198.

- BMC Oral Health. 2014 Jul 29;14:92. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-92. Self-induced vomiting and dental erosion—a clinical study. Uhlen MM1, Tveit AB, Stenhagen KR, Mulic A.

- J Am Dent Assoc. 2012 Mar;143(3):278-85. Quantitative analysis of tooth surface loss associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a longitudinal clinical study. Tantbirojn D, Pintado MR, Versluis A, Dunn C, Delong R.

- J Am Dent Assoc. 2006 Feb;137(2):160-9. Interdisciplinary management of anterior dental esthetics. Spear FM, Kokich VG, Mathews DP.

- Dahl BL, Krogstad O: Long term observations of an increased occlusal face height obtained by a combined orthodontic/prosthetic approach. J Oral Rehab 1985; 12: 173–176.

- Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2009 May-Jun; 24(3):497-501. Altered vertical dimension of occlusion: a comparative retrospective pilot study of tooth- and implant-supported restorations. Ormianer Z, Palty A.

- Dent Clin North Am. 2007 Apr; 51(2):487-505, x-xi. A multidisciplinary approach to esthetic dentistry. Spear FM, Kokich VG.

- J Am Dent Assoc. 2008 Jun; 139(6):725-33. Using orthodontic intrusion of abraded incisors to facilitate restoration: the technique’s effects on alveolar bone level and root length. Bellamy LJ, Kokich VG, Weissman JA.

- J Esthet Restor Dent. 2009; 21(2):96-111. The apparent contact dimension and covariates among orthodontically treated and nontreated subjects. Raj V1, Heymann HO, Hershey HG, Ritter AV, Casko JS.

SPEAR STUDY CLUB

Join a Club and Unite with

Like-Minded Peers

In virtual meetings or in-person, Study Club encourages collaboration on exclusive, real-world cases supported by curriculum from the industry leader in dental CE. Find the club closest to you today!

By: Frank Spear

Date: December 10, 2015

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts