Orthodontic vs. Restorative: Correction of Mal-Aligned Anterior Teeth

Every dentist has heard a patient say, “I don’t want orthodontics, can’t you make my teeth look better without me needing to wear braces?” The answer is sometimes yes and sometimes no, but how do you decide?

You need to ask six questions before making the decision and convey information that may be helpful in your conversations with patients. What I know for sure is that some patients with malaligned teeth can be treated with only restorative dentistry and get an excellent result, while others would be much better off with orthodontics.

I also know that if a patient says, “I don’t want braces,” there’s still a chance they will.

Question 1: Will the teeth need to be restored even if orthodontics is completed?

One of orthodontics’ greatest benefits is that it can often eliminate the need for restorative dentistry, a great savings in terms of dollar cost and tooth structure.1–3 But if the teeth will need to be restored anyway, there has to be a compelling reason to do the orthodontics — something it brings that eliminates some other negative aspect that restorative dentistry alone can’t solve.

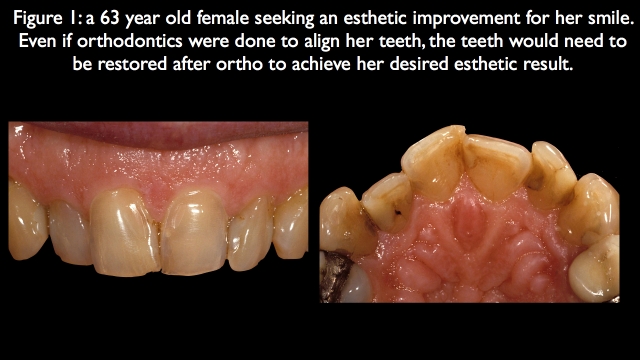

The patient in Fig. 1 is a perfect example of this question. She has very unesthetic anterior teeth in color, facial erosion, and failing old restorations. Even if orthodontics were completed to align her teeth more ideally, she still would need the teeth restored. In her case, orthodontics wouldn’t eliminate the restorative need, and all the other parameters didn’t need orthodontics aside from correcting the alignment issue. She was treated with restorative dentistry (Fig. 2).

Question 2: Can the occlusion be managed acceptably without orthodontics?

This question addresses whether the occlusion can be developed to a functional level for that patient without orthodontics; it doesn’t necessarily mean the patient should have an ideal Class I molar or Class I canine relationship.

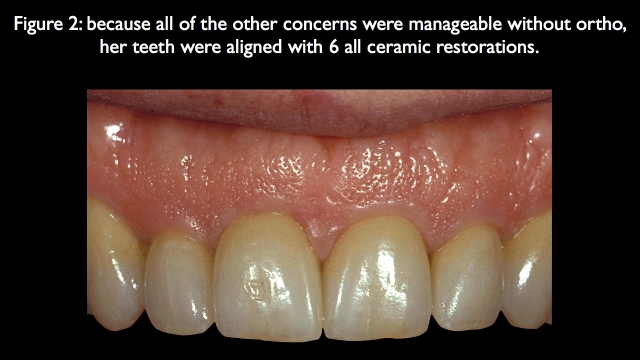

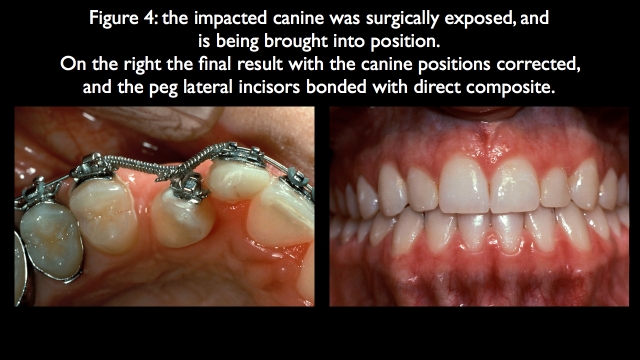

The patient in Fig. 3 is a good example: She’s very young, in her early 20s, with an impacted maxillary right canine and peg lateral incisors. In addition, the mandibular right canine is in cross-bite with the pegged lateral. She presented for a second opinion regarding the impacted canine.

The first opinion was to devitalize the mandibular right canine, warp it to the lingual with a crown as much as possible to jump the cross-bite, extract the impacted canine, then do a three-unit fixed partial denture from the maxillary right first premolar to the maxillary right pegged lateral. This initial plan would be compromised functionally over her life’s remaining 70–80 years.4

Instead, she was treated conservatively with surgical exposure of the impacted canine, orthodontics to bring it into position and correct the occlusion, and direct composites on the pegged lateral incisors (Fig. 4).

Question 3: Is the most apical papilla level esthetically acceptable?

This question is subtle and involves gingival esthetics, specifically the levels of the interdental papilla. It’s important because it’s easy to surgically position a papilla, which is often necessary in cases of anterior wear with secondary eruption, resulting in the teeth and soft tissues being coronally positioned.

However, it’s tough to surgically move a papilla coronally, and it’s actually impossible if the reason for the apically positioned papilla is tooth alignment, such that the interdental contacts extend too far apically. For this reason, if the most apically positioned papilla isn’t acceptable, orthodontics is typically the only option for correction. This is also true if the papilla is apically positioned due to interproximal bone loss, where extruding the adjacent teeth and equilibrating their edges as they erupt can move bone and soft tissue in a more coronal direction.

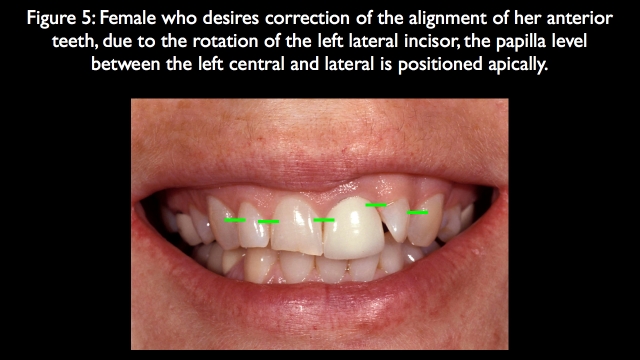

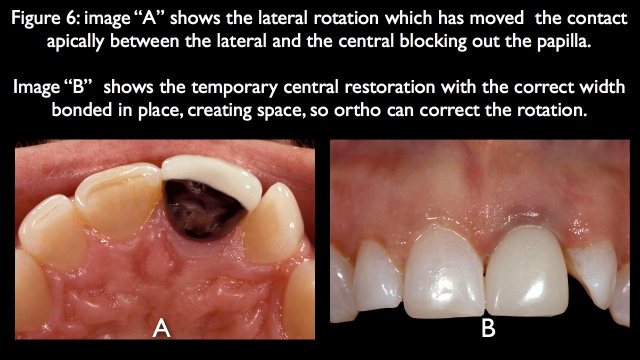

The patient in Fig. 5 is a good example of this question. She stated she wanted an ideal smile with 10 veneers and didn’t want orthodontics; however, the papilla between the left central and lateral incisors is positioned apically because the rotation of the lateral incisor (Fig. 6).

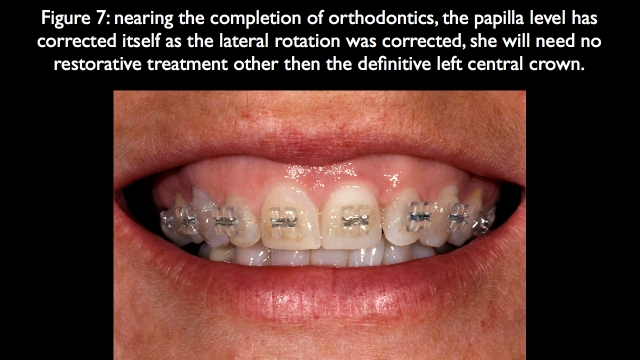

The patient had stated very clearly that she wouldn’t do orthodontics, but after we helped her see that without orthodontics there would be a significant asymmetry between how the right and left sides looked after restoration, and that if she did the orthodontics she’d only have to restore one tooth, the left central, she did orthodontic treatment. Because this is a tooth position problem, not bone, the papilla moved into an ideal position as the lateral rotation was corrected5,6 (Fig. 7).

Question 4: Is the most apical gingival margin level acceptable?

This question is similar to the third question but involves the gingival margin levels. The most significant difference between these questions is that it is very predictable to graft facial gingival margin levels in a coronal direction if the root surface is exposed.

In other words, grafting is an excellent choice if the gingival margin is too far apical because of recession but the tooth is positioned correctly. However, if the most apical gingival margin level is unacceptable due to a lack of adequate eruption and the tooth has no recession, orthodontic extrusion to bring the tooth and tissue coronally is usually the only predictable option.7,8

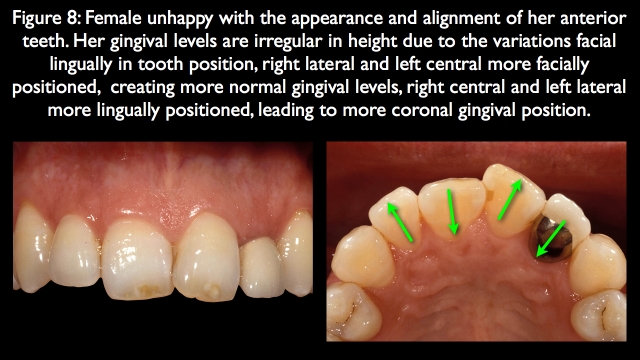

The patient in Fig. 8 is a great example of this. She presented with irregular gingival margin levels but the most apically positioned gingival margins — the canines and left central — are acceptable and don’t need to be moved coronally. Instead, the more coronally positioned gingival margins on the right central and left lateral need to be moved apically, which can be done without orthodontics.

But it’s important to ask why the patient’s gingival margins are irregular — she has no tooth wear that would have led to secondary eruption, and the eruption looks relatively normal when comparing incisal-edge positions. Instead, you see the variations in the facial lingual position of the anterior teeth when looking from an occlusal view. This leads to variations in facial gingival thickness, sulcus depth, and gingival margin position. The right lateral and left central are positioned a bit to the facial, which thins the tissue. This results in a facial sulcus depth of around 1 mm and more apically positioned gingival margins.

The right central and left lateral incisors are positioned significantly to the lingual, resulting in thicker tissue, deeper sulcus depths, and more coronally positioned gingival margins. The sulcus on the right central probes is 2.5 mm, and the sulcus on the left lateral probes is 4 mm.

In these cases, the challenge of not doing orthodontics is managing the long-term postsurgical gingival margin position, because surgery is correcting only the gingival margin position, not the underlying root position. This patient chose the nonorthodontic option.

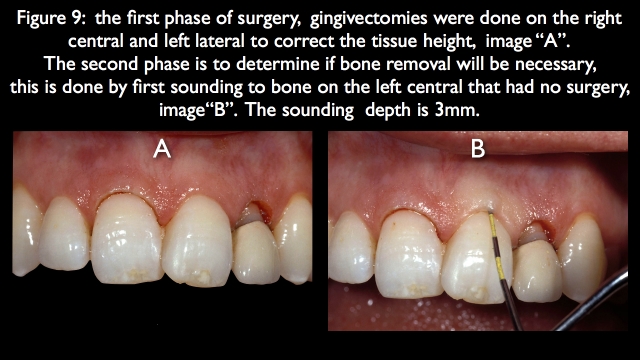

The first step in the surgical correction was to perform gingivectomies on the right central and left lateral, idealizing the gingival margin position. In addition, the soft tissue dimension above bone on the left central, which had no surgery, was measured at 3 mm using sounding9 (Fig. 9).

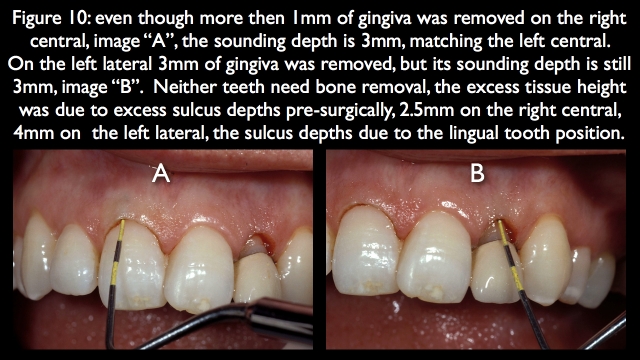

The next step in the surgery is to sound bone on the right central and left lateral, comparing the measurement to the normal left central. Even though the right central had 1.5 mm of gingiva removed and the left lateral 3 mm of tissue removed, both of their sounding depths remained 3 mm, indicating no bone removal is necessary (Fig. 10). The problem is that the roots are to the lingual, and the tissue will want to rebound.

Had orthodontics been used to correct the facial lingual position, the gingiva would have been correctly positioned and stable. Because it was done surgically and the teeth are to the lingual, the facial restorative emergence profile must be reasonably prominent to avoid the rebound.10 The 10-year recall photograph of the final result shows an acceptable result on the right central, but definite inflammation and redness on the left lateral (Fig. 11).

Question 5: Can an acceptable contour and arrangement be created without orthodontics?

This question addresses something I’m asked frequently during workshops or seminars: A student walks up with a set of models and asks, “Do you think I can do this case without orthodontics?” The models typically show very crowded teeth or teeth with large diastemas present. Often in crowding cases, the papilla levels or the gingival margin levels will dictate the need for orthodontics if an ideal result is desired. But regardless of the presentation of crowding or diastemas, the definitive way to identify what is possible is to perform a diagnostic wax-up.

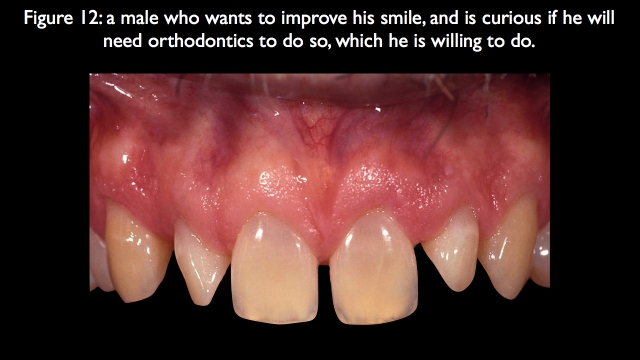

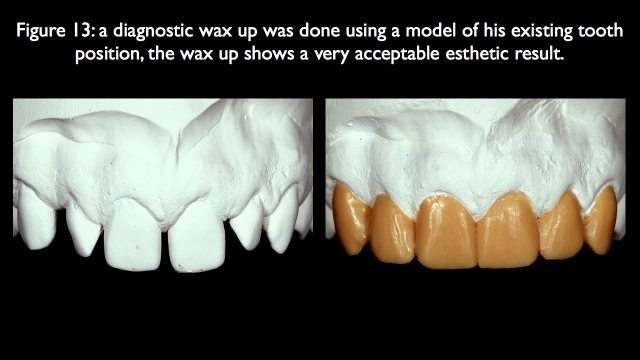

The patient in Fig. 12 is a perfect example. He presented with pegged lateral incisors and large diastemas in the maxillary and mandibular anterior regions. He desires an improved smile and is willing to do orthodontics. He is in his 50s, has no occlusal or functional issues, and his papilla and gingival margin levels are acceptable. Orthodontics could potentially eliminate the need to veneer the centrals and canines, because the laterals would need to be restored regardless.

I presented the orthodontic versus non-orthodontic option and explained that the only way to truly visualize the result would be a diagnostic wax-up, which the lab completed (Fig. 13). The wax-up shows that the spacing is easily managed without any need for orthodontics.

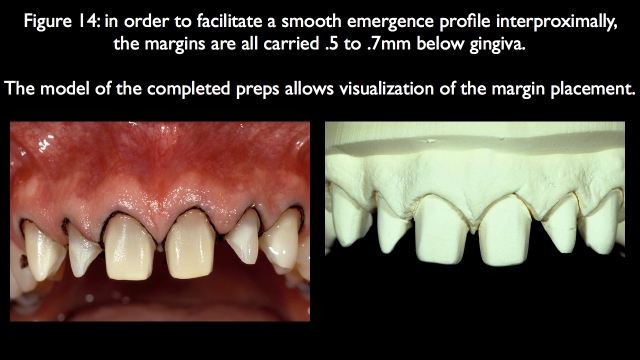

The challenge of diastema closure cases with restorations is carrying the restoration subgingival on the interproximal. If you don’t, you get essentially a ledge, or an overhang of restorative material when carrying the contact to the tip of the papilla. In addition, the papilla will remain more blunted instead of taking on an ideal form. I find it easiest to manage the subgingival margin position with retraction cord, carrying the prep margin 0.5 to 0.7 mm below tissue (Fig. 14).

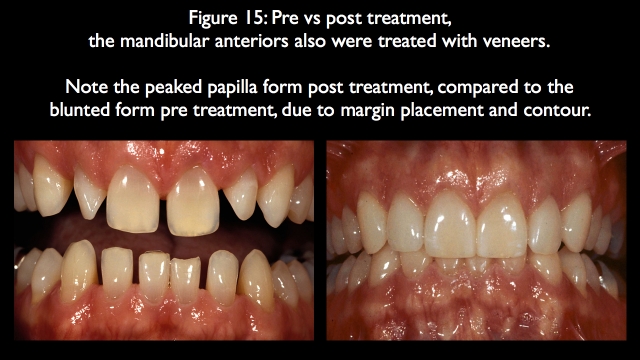

This allows the laboratory to create a much smoother emergence profile interproximally, leading to a better papilla form in the final result (Fig. 15).

Question 6: Can the restorations be done without structurally debilitating the teeth if orthodontics isn’t completed?

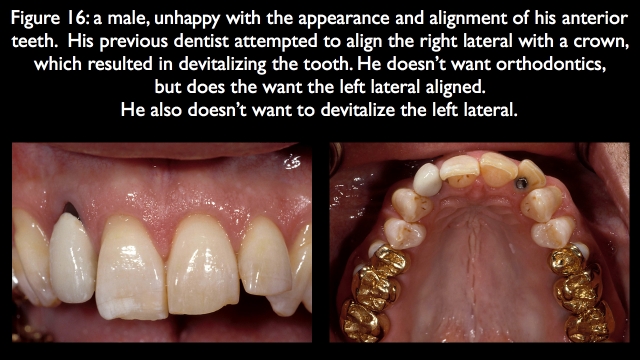

This question typically arises when significant tooth preparation is necessary to correct tooth malalignment, such as the facially inclined left lateral incisor (Fig. 16).

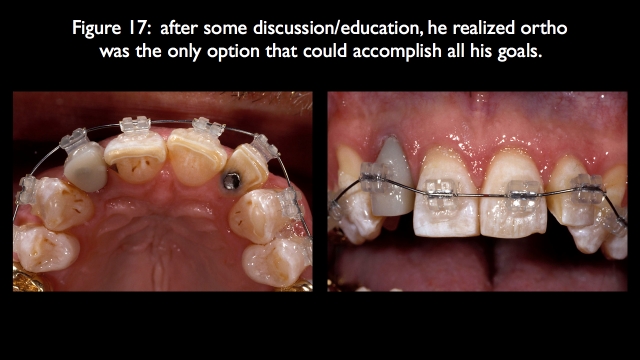

The patient is a male in his 50s who desires a more pleasing smile, correcting the malalignment of the anterior teeth. The position of his left central is ideal from a facial lingual perspective, so the plan is to move the right central to the facial and the left lateral to the lingual. The problem is, the patient doesn’t want orthodontics. Prepping the left lateral enough to align it will not only devitalize the tooth but also leave minimal tooth left to retain the restoration.

I presented the option of leaving the lateral out to the facial to avoid the endo, but he didn’t want that, either. He had already had a dentist try to align the right lateral with a crown and ended up requiring endo, so he chose the orthodontic option (Fig. 17).

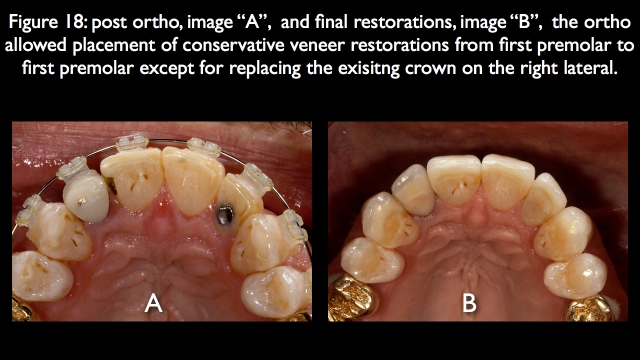

Because the orthodontics corrected the facial lingual inclination issues of all the anterior teeth, conservatively prepped veneers were used to correct the final position and appearance of all the teeth except the previously crowned right lateral (Fig. 18).

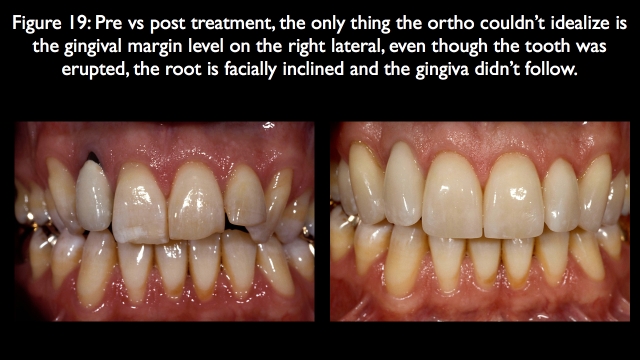

The one thing orthodontics doesn’t always predictably correct is facial gingival margin levels. In his case, the previously crowned right lateral had its gingival margin level too far apically positioned, because the root is facially inclined. Eruption was used during the orthodontics to try to move the gingival margin level to a more coronal position; the tooth erupted but the facial gingiva didn’t move11,12 (Fig. 19).

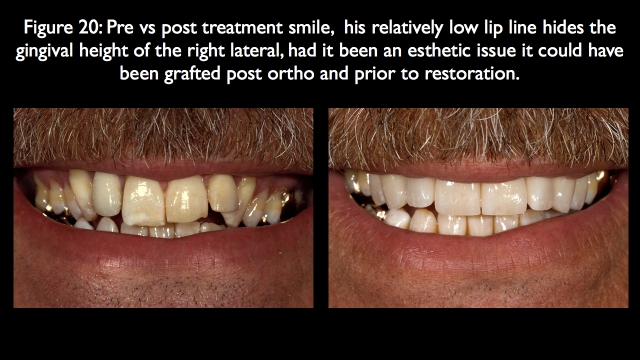

The eruption exposed the root, so had it been critical to have the right lateral gingival level ideal, it would now be possible to move it coronally with grafting. Because his high lip line never showed the gingival levels, it was left as is, and the restoration was carried out to the gingiva to hide the dark root (Fig. 20).

This article aims to help you think through why you might consider orthodontics alone or in conjunction with restorative dentistry to help you treat your patients. These six questions will give you a structure for that thought process.

References

- Joss‐Vassalli, I., Grebenstein, C., Topouzelis, N., Sculean, A., & Katsaros, C. (2010). Orthodontic therapy and gingival recession: a systematic review. Orthodontics & craniofacial research, 13(3), 127-141.

- Jacobson, N., & Frank, C. A. (2008). The myth of instant orthodontics: an ethical quandary. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 139(4), 424-434.

- Friedman, M. J. (1998). A 15-year review of porcelain veneer failure–a clinician’s observations. Compendium of continuing education in dentistry (Jamesburg, NJ: 1995), 19(6), 625-8.

- Friedman, M. J. (2001). Masters of esthetic dentistry: Porcelain veneer restorations: An clinician’s opinion about a disturbing trend. Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry, 13(5), 318.

- De Backer, H., Van Maele, G., Decock, V., & Van den Berghe, L. (2007). Long-Term Survival of Complete Crowns, Fixed Dental Prostheses, and Cantilever Fixed Dental Prostheses with Posts and Cores on Root Canal-Treated Teeth. International Journal of Prosthodontics, 20(3).

- Spear, F. M. (2006). Interdisciplinary esthetic management of anterior gingival embrasures. Advanced Esthetic & Interdisciplinary Dentistry, 2, 20-28.

- Tarnow, D. P., Magner, A. W., & Fletcher, P. (1992). The effect of the distance from the contact point to the crest of bone on the presence or absence of the interproximal dental papilla. Journal of Periodontology, 63(12), 995-996.

- Yoshinuma, N., Sato, S., Makino, N., Saito, Y., & Ito, K. (2009). Orthodontic extrusion with palatal circumferential supracrestal fiberotomy improves facial gingival symmetry: a report of two cases. Journal of Oral Science, 51(4), 651-654.

- Carvalho, C. V., Bauer, F. P. F., Romito, G. A., Pannuti, C. M., & De Micheli, G. (2006). Orthodontic extrusion with or without circumferential supracrestal fiberotomy and root planing. International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry, 26(1).

- Gargiulo, A. W., Wentz, F. M., & Orban, B. (1961). Dimensions and relations of the dentogingival junction in humans. The Journal of Periodontology, 32(3), 261-267.

- Deas, D. E., Moritz, A. J., McDonnell, H. T., Powell, C. A., & Mealey, B. L. (2004). Osseous surgery for crown lengthening: A 6‐month clinical study. Journal of Periodontology, 75(9), 1288-1294.

- Rana, T. K., Phogat, M., Sharma, T., Prasad, N., & Singh, S. (2014). Management of gingival recession associated with orthodontic treatment: a case report. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR, 8(7), ZD05.

SPEAR STUDY CLUB

Join a Club and Unite with

Like-Minded Peers

In virtual meetings or in-person, Study Club encourages collaboration on exclusive, real-world cases supported by curriculum from the industry leader in dental CE. Find the club closest to you today!

By: Frank Spear

Date: March 23, 2017

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts