Evaluating Facial Esthetics: The Esthetic Plane

In my previous article in this series, I discussed the facial profile and how evaluating it using glabella, sub-nasal, and pogonion could help assess whether orthognathic surgery would be an appropriate consideration for correcting occlusal and esthetic problems.

In this article, I will look at the profile again but from a different perspective — what I call facial balance. From a profile perspective, the concept of having a specific relationship between the nose, lips, and chin goes back to the 1950s and the work of the orthodontist Dr. Robert Ricketts. Dr. Ricketts was concerned that in the name of occlusion and alignment, orthodontists were actually making the esthetic appearance of some patients worse by not paying attention to what he called the esthetic plane, or “E plane.”

Dr. Robert Ricketts and the origins of the “E plane”

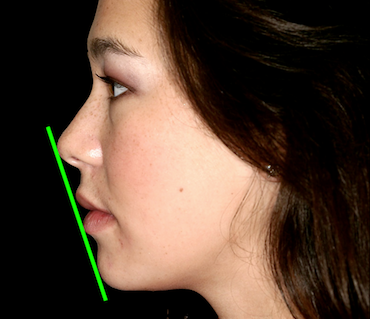

Fundamentally, the “E plane” is simply a line drawn from the nose’s tip to the chin’s tip. Dr. Ricketts’ key assessment was to look at how the upper and lower lip related to that line. He believed that to have a pleasing facial profile, in the average Caucasian face the lower lip would be 2 mm behind the line and the upper lip 4 mm behind the line — with variations being normal for patients of different ethnic backgrounds but with some commonalities applying to all patients.

Understanding the E plane and lip position

Those commonalities would be that the closer to the E plane the lips are — in some cases even being anterior to the plane — the lips and teeth will dominate the smile, with the nose and chin appearing weak. And the farther behind the plane the lips are, the more likely the nose and chin will dominate the smile. The key was to evaluate the E plane relationship before performing orthodontic treatment.

Clinical applications: Extractions vs. expansion

An example of how the E plane would be used is a patient with significant upper and lower arch crowding. The clinician must decide whether to consider extracting teeth, such as first premolars, or expanding the arch. If the lips in profile were on or in front of the E plane, the decision would be extraction and anterior retraction, improving the relationship between the lip and the E plane. If, on the other hand, the lower lip is 6 mm behind the E plane, the decision would be to align the teeth and expand the arch, moving the anterior teeth and lips to a more anterior and prominent position.

For the non-orthodontist, the E plane assessment is also valuable. In general, the closer the lips are to the E plane, the more dominant the teeth and lips will appear; the farther behind the E plane the lips are, the more dominant the nose and chin appear.

Restorative considerations: Tooth size and shade

As a rule, I always consider these relationships when looking at the size and shape of the anterior teeth in any restoration. Using the central incisor as a reference, we know that the range of normal unworn central incisor lengths in humans is 9–12 mm, with 10.5 mm being the average. I may alter that size for a patient anywhere from 10 to 12 mm, based upon the E plane and some additional findings. Suppose the patient’s profile appears very convex — the lips are on or anterior to the “E” plane. In that case, you must be careful not to make anterior teeth too large or too white, because the teeth in this profile will already dominate the smile.

Concave profiles: Enhancing anterior prominence

For concave profiles, where the lips are well behind the E plane, it may be beneficial to increase the anterior tooth size both in length and facial prominence with your restoration. In addition, these patients often benefit from a slightly lighter final shade, again to provide better balance with the strong nose and chin.

Beyond the E plane: What comes next

The E plane isn’t the only factor affecting final tooth size and shade choice. In a future article, we’ll discuss the impact of lip fullness and mobility as additional elements of our assessment that will affect how we restore anterior teeth regarding size and shade.

VIRTUAL SEMINARS

The Campus CE Experience

– Online, Anywhere

Spear Virtual Seminars give you versatility to refine your clinical skills following the same lessons that you would at the Spear Campus in Scottsdale — but from anywhere, as a safe online alternative to large-attendance campus events. Ask an advisor how your practice can take advantage of this new CE option.

By: Frank Spear

Date: March 9, 2017

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts