The Diagnosis-First Approach to Occlusal Splints

Occlusal splints are prescribed to manage muscle activity, reduce the force on the temporomandibular joint, stimulate growth, and increase the size of the oropharynx in patients suffering from airway-disordered breathing. The design varies depending on the intended use of the orthotic, and it is essential to diagnose the problem before recommending and designing the splint.

Choosing the right splint for your patient

Dylina et al. defined occlusal therapy as ”the art and science of establishing neuromuscular harmony in the masticatory system and creating a mechanical advantage for parafunctional forces with a removable appliance.“ But why is there instability in the system? The occlusal masticatory system includes the teeth, muscles, temporomandibular joints and, indirectly, the airway. The type of appliance is dependent on what needs to be treated. We will explore three here: the directive splint, the anterior bite plane splint, and the flat-plane stabilizing splint.

The directive splint

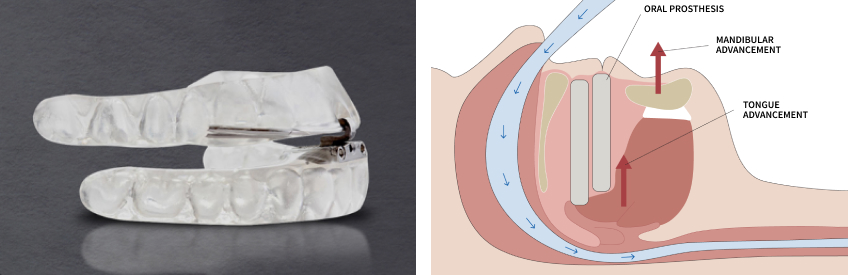

Splints can be categorized as partial, full-coverage, hard, soft, stabilization, and directive. Directive splints are designed to position the mandible in a predetermined location. Two uses of a directive splint are to improve the airway’s size and stimulate growth. A mandibular advancement appliance (MAD) protrudes the mandible, inducing changes in the tongue, soft palate, and pharynx, hoping to improve airway patency (Fig. 1).

In a study by Marinez-Gomis et al., the acceptance rate after one year ranged from 55% to 82%. The reasons for discontinuing use are a lack of efficiency, side effects, and complications. While a MAD can be used as a treatment option for CPAP, it can also determine if an anatomical change is needed to resolve the airway issue. The Seattle Protocol, developed by Spear Resident Faculty members Dr. Jeff Rouse and Dr. Gregg Kinzer, is an example of determining if an anatomical change will resolve the airway disturbance before definitive treatment is recommended.

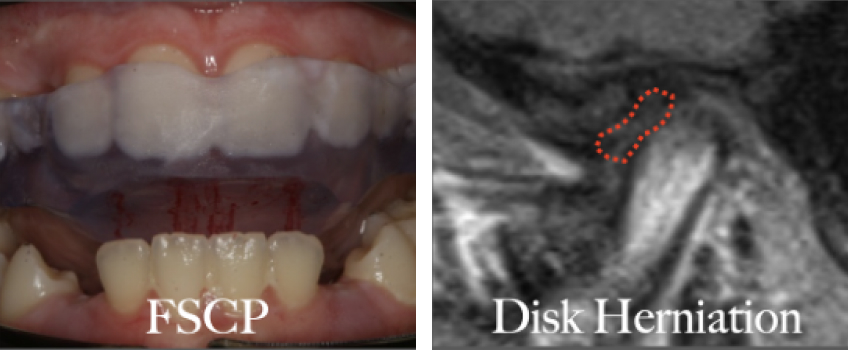

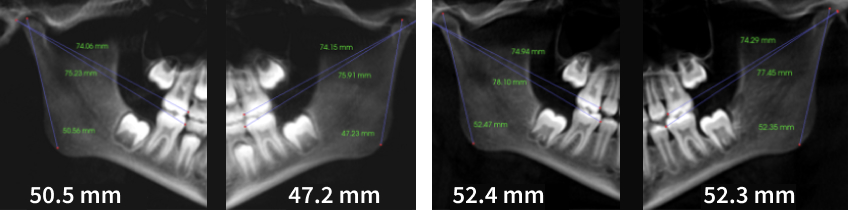

A directive splint can also stimulate growth in the Class II adolescent patient. However, clinical effectiveness is unpredictable without understanding when growth is possible. It’s imperative that the condyle is positioned under the disk (in the treatment position) and that growth potential remains before prescribing a directive splint to stimulate growth (Figs. 2a–2c). Holding the condyle down and forward without the protection of the disk can alter the condylar tissue’s oxygenation, nutrition, and lubrication due to synovial fluid changes, disturbing growth in the condyle and increasing the stress on the articular cartilage. The growth disturbance can decrease the condyle’s vertical dimension, resulting in an exaggerated Class II skeletal relationship.

While directive splints have their place in practice, splints are more often prescribed to treat parafunctional activities such as sleep bruxism and clenching. Parafunction is defined as excessive mechanical strain due to abnormal occlusal pressure. Our bodies are equipped with a self-protective reflex, including the periodontal fibers that induce negative feedback on the activity of muscle spindles. When muscle activity exceeds the self-protective reflex, a splint can provide an advantage in reducing stress on the teeth and temporomandibular joints by changing the bite touch state between the maxillary and mandibular teeth.

Parafunction was thought to be caused by stress and anxiety, but recent studies believe it may be multifactorial. Genetics, stress, malocclusion, airway, and temporomandibular joint changes may all affect muscle hyperactivity, and it is the dentist’s responsibility to determine the cause of the parafunction before recommending treatment. Splints to manage bruxism due to sleep disturbances have been addressed, but it’s imperative to undertsand why muscles are sore before designing the splint. Airway sympathetic hyperactivity, changes in occlusion due to a structural change in the TMJs, and uncontrollable clenching will determine the splint design.

The anterior bite plane splint

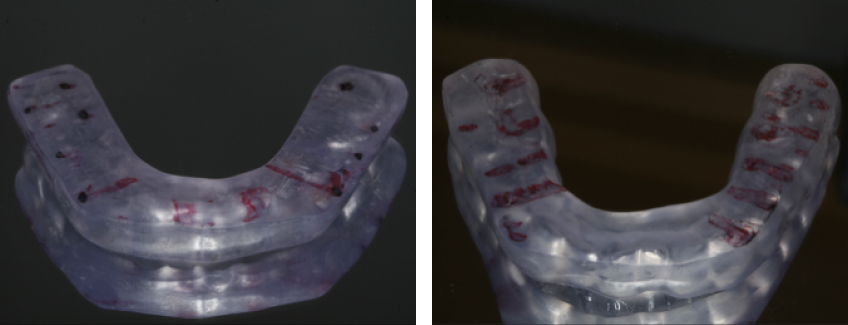

An anterior bite plane splint (Fig. 3) is a diagnostic tool and therapeutic measure to manage muscle forces associated with TMJ issues. Studies have indicated a notable masseter and temporalis muscle activity reduction, up to 50%, when occluding exclusively on the anterior teeth. This decrease is attributed to differences in afferent feedback from the periodontal fibers in the anterior and posterior teeth. For instance, in a study by Johnsen et al., occlusion solely on the anterior teeth resulted in a 50% reduction in muscle force. Additionally, this approach eliminates posterior tooth interferences, facilitating the attainment of a fully seated condylar position.

While anterior bite plane appliances are favored for their ease of fabrication and adjustments, caution is warranted during prolonged use. Although effective in reducing muscle fatigue and protecting the dentition, extended use may increase forces on the temporomandibular joints. This can be particularly problematic for patients with preexisting structural changes in the TMJ. Turp’s study, which used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess disk position, found that 25% of TM joints exhibited anteriorly displaced disks. Theoretically, heightened forces on a structurally altered TMJ may destabilize an already adapted joint.

Another potential concern associated with the prolonged use of anterior bite plane splints is the risk of tooth movement. The absence of posterior tooth contact may lead to the posterior dentition’s extrusion, the anterior dentition’s intrusion, or a combination of both, resulting in an anterior open bite.

The flat-plane stabilizing splint

A primary use for a flat-plane splint is the management of muscle, temporomandibular joint instability, to facilitate an optimal condylar position before definitive restorative treatment and protect the teeth from pathological tooth wear due to bruxism. The splint design should provide an environment of stability between the muscles, temporomandibular joint, and teeth. Although the design is dependent on the area targeted, the goal is to manage the weak part of the system, and a diagnosis needs to be determined before initiating splint therapy.

The clinical examination is the first step in diagnosing the occlusal masticatory system and will determine if further diagnostic information is needed before starting splint therapy. While beyond the scope of this article, imaging of the temporomandibular joints may be necessary and is warranted when there is a Class II occlusion greater than 2–3 mm. A Class II occlusal relationship greater than 2–3 mm can indicate a structurally altered temporomandibular joint, and verifying stability is necessary before proceeding with definitive restorative treatment.

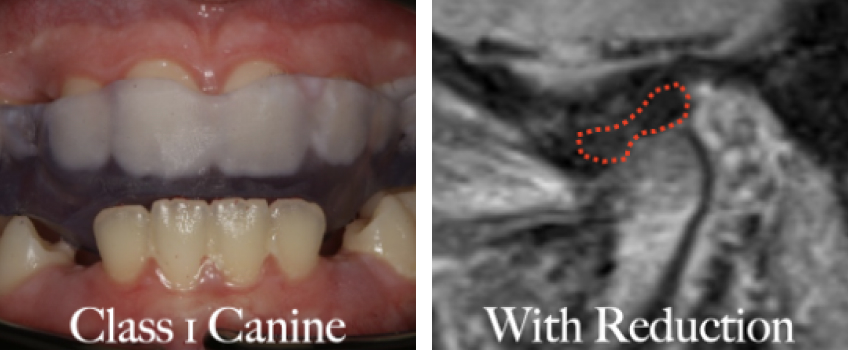

When managing muscle force, the splint design should include equal simultaneous contacts on all teeth in the fully seated condylar position (FSCP) with immediate posterior disclusion in excursive movements or anterior guidance (Fig. 4a). A study by Johnson et al. showed that the magnitude of force more than doubled when occluding on the molar teeth compared to the anterior teeth. The periodontal mechanoreceptors on the anterior and posterior teeth affect the force levels. While the muscle force is decreased upon excursive movements, the equal and simultaneous tooth structure distributes the load amongst all the teeth in the FSCP, balancing the effect of the muscle forces.

If the weak part of the system is determined to be a structurally altered temporomandibular joint, the splint design should be designed to reduce the force placed on the joint, sacrificing muscle force (Fig. 4b). The adjustment in the FSCP will be the same as the anterior guidance splint, with equal simultaneous contacts; the difference is group function is incorporated into excursive movements.

Group function will increase muscle forces but reduce the forces in the TMJs. This was demonstrated by Rues et al. utilizing biomechanical modeling. They showed that the mandible functions as a Class III lever, and the forces at the joint level are less when the bite force is directed over the posterior teeth.

Long-term muscle force reduction has been a controversial debate. Studies suggest no decreased muscle activity after two to six weeks. A study by Solberg et al. measuring nocturnal masseteric muscle activity with EMG showed a reduction in muscle activity immediately after the insertion of a full-arch splint. The muscle forces remained low until the splint was removed, when the EMG values returned to pretreatment levels. However, there was a dramatic reduction in symptoms, suggesting the nocturnal relaxation of muscle activity provided a period of relaxation, potentially reducing inflammation in the muscles and temporomandibular joints.

Leading with diagnosis in occlusal splint therapy

Occlusal splints are a good alternative to managing pathological muscle, TMJ, and parafunctional activities. It is essential to understand what area is being treated before starting treatment, and that the diagnosis of the temporomandibular joints will dictate the splint design. While the long-term reduction of forces is debatable, studies have shown decreased symptoms and adaptation of the occlusomasticatory system utilizing splint therapy.

References

- Türp, J. C., Schlenker, A., Schröder, J., Essig, M., & Schmitter, M. (2016). Disk displacement, eccentric condylar position, osteoarthrosis–misnomers for variations of normality? Results and interpretations from an MRI study in two age cohorts. BMC Oral Health, 16(1), 124.

- Dylina, T. J. (2001). A common-sense approach to splint therapy. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 86(5), 539-545.

- Martínez-Gomis, J., Willaert, E., Nogues, L., Pascual, M., Somoza, M., & Monasterio, C. (2010). Five years of sleep apnea treatment with a mandibular advancement device: side effects and technical complications. The Angle Orthodontist, 80(1), 30-36.

- Dalewski, B., Chruściel‐Nogalska, M., & Frączak, B. (2015). Occlusal splint versus modified nociceptive trigeminal inhibition splint in bruxism therapy: a randomized, controlled trial using surface electromyography. Australian Dental Journal, 60(4), 445-454.

- Rues, S., Lenz, J., Türp, J. C., Schweizerhof, K., & Schindler, H. J. (2011). Muscle and joint forces under variable equilibrium states of the mandible. Clinical Oral Investigations, 15(5), 737-747.

- Alkhutari, A. S., Alyahya, A., Conti, P. C. R., Christidis, N., & Al-Moraissi, E. A. (2021). Is the therapeutic effect of occlusal stabilization appliances more than just placebo effect in the management of painful temporomandibular disorders? A network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 126(1), 24-32.

- Tanaka, Y., Yoshida, T., Ono, Y., & Maeda, Y. (2021). The effect of occlusal splints on the mechanical stress on teeth as measured by intraoral sensors. Journal of Oral Science, 63(1), 41-45.

- Albagieh, H., Alomran, I., Binakresh, A., Alhatarisha, N., Almeteb, M., Khalaf, Y., … & Alqahatany, M. (2023). Occlusal splints-types and effectiveness in temporomandibular disorder management. The Saudi Dental Journal, 35(1), 70-79.

- Stapelmann, H., & Türp, J. C. (2008). The NTI-tss device for the therapy of bruxism, temporomandibular disorders, and headache–Where do we stand? A qualitative systematic review of the literature. BMC Oral Health, 8(1), 22.

- Nebbe, B., Major, P. W., & Prasad, N. G. N. (1998). Adolescent female craniofacial morphology associated with advanced bilateral TMJ disc displacement. The European Journal of Orthodontics, 20(6), 701-712.

- Al-Moraissi, E. A., Farea, R., Qasem, K. A., Al-Wadeai, M. S., Al-Sabahi, M. E., & Al-Iryani, G. M. (2020). Effectiveness of occlusal splint therapy in the management of temporomandibular disorders: network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 49(8), 1042-1056.

- Johnsen, S. E., Svensson, K. G., & Trulsson, M. (2007). Forces applied by anterior and posterior teeth and roles of periodontal afferents during hold-and-split tasks in human subjects. Experimental Brain Research, 178(1), 126-134.

SPEAR campus

Hands-On Learning in Spear Workshops

With enhanced safety and sterilization measures in place, the Spear Campus is now reopened for hands-on clinical CE workshops. As you consider a trip to Scottsdale, please visit our campus page for more details, including information on instructors, CE curricula and dates that will work for your schedule.

By: Curt Ringhofer

Date: July 9, 2024

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts