A Crash Course in Dental Cements for Restorative Procedures

With so many dental cements on the market, it can be overwhelming for restorative dentists to know what type of cement to use. With each choice comes questions like: Should this cement be light-cured? Is this a dual-cure cement? Would you happen to know if any pre-treatment of the tooth is required? And, of course, one of the most critical questions of all: Should this restoration be bonded in, or can I lute it? This article provides an overview of dental cement classification so restorative dentists can select the most appropriate cement.

The Two Main Categories of Dental Cement

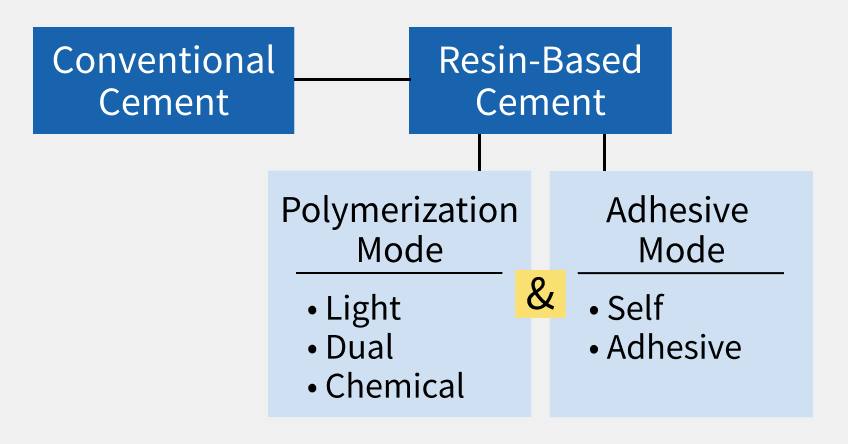

There are several ways cements can be classified. But for simplicity’s sake, there are two overarching categories (Fig. 1).

As shown in Fig. 1, cements can be either conventional or resin-based cements1,2.

Conventional Dental Cements

Conventional cements include glass ionomer, resin-modified glass ionomer (RMGI), zinc phosphate, or modified zinc oxide eugenol3. 3M™ Ketac ™ Cem is an example of a glass ionomer cement, while GC’ s FujiCEM 2 Resin Glass Ionomer is an RMGI cement. Mechanical retentive features may be required if using a conventional cementation adhesive strategy. In effect, the preparation for a molar may require about 4.0 mm of axial wall height (AWH) and about 10-20 degrees of taper, while the preparation for an anterior tooth will require 3.0 mm AWH and relatively parallel axial walls4. Conventional cement should not be used with non-retentive indirect restorations such as veneers, overlays, onlays, or resin-bonded fixed dental prostheses (FDPs).

Resin-Based Dental Cements

The second overarching category of cement is resin-based cement. To confuse matters, the cement then defines its adhesion and polymerization mode. For example, a cement may be defined as an “adhesive, dual-cure cement.” The mode of adhesion can be self-adhesive or adhesive. The polymerization mode can be either chemical, light, or dual (both chemical and light)5. A list of common resin-based cements is found (Fig. 3).

| Brand Name | Adhesive Mode | Polymerization Mode |

| 3M™ RelyX ™ Unicem 2 | Self-Adhesive | Dual-Cure |

| Kuraray PANAVIA ™ SA Cement Universal | Self-Adhesive | Dual-Cure |

| Ivoclar Variolink ™ Esthetic DC | Adhesive | Dual-Cure |

| Ivoclar Variolink ™ Esthetic LC | Adhesive | Light-Cure |

| Kuraray PANAVIA ™ V5 | Adhesive | Dual-Cure |

| 3M™ RelyX ™ Universal | Adhesive and Self-Adhesive | Dual-Cure |

| Ivoclar Multilink ™ Automix | Adhesive | Chemical-Cure with light cure option |

| Kuraray PANAVIA ™ 21 | Adhesive | Chemical-Cure |

Figure 3: Common resin-based cements.

Self-adhesive cements do not require the tooth to be treated with an acid etch or the application of a dental adhesive, while adhesive cements do6. However, while the tooth does not require treatment, the indirect restoration (whether lithium disilicate, zirconia, hybrid ceramic, etc.) should still be pre-treated according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Chemically cured cements are self-polymerizing through a chemical reaction that typically uses peroxide, while light-cured cements use photo-initiators and light. A chemically cured or a dual-cure cement is preferred in scenarios of a deep restoration or where the restorative material attenuates light. Examples of this situation may be the cementation of a fiber post or the delivery or the bonding of the zirconia crown. The advantage of light-cured cement is the operator can control the setting time. Light-cured cements should be limited to indirect restorations that are 1.5-2.0 mm thick or less7. This minimum thickness requirement may be less for zirconia.

Dental Cements for Restorative Procedures

The market for restorative materials, including dental cements, is ever evolving. The best strategy for familiarizing yourself with your material is to reference the manufacturer’s instructions for use (IFUs).

References

- Pameijer, C. H. (2012). A review of luting agents. International Journal of Dentistry, 2012(1), 752861.

- Heboyan, A., Vardanyan, A., Karobari, M. I., Marya, A., Avagyan, T., Tebyaniyan, H., … & Avetisyan, A. (2023). Dental luting cements: an updated comprehensive review. Molecules, 28(4), 1619.

- Wingo, K. (2018). A review of dental cements. Journal of Veterinary Dentistry, 35(1), 18-27.

- Shillingburg, H. T., Hobo, S., Whitsett, L. D., Jacobi, R., & Brackett, S. E. (1997). Fundamentals of Fixed Prosthodontics (Vol. 194). Chicago, IL, USA: Quintessence Publishing Company.

- Stamatacos, C., & Simon, J. F. (2013). Cementation of indirect restorations: an overview of resin cements. Compendium of Continuing Education in Dentistry (15488578), 34(1).

- Radovic, I., Monticelli, F., Goracci, C., Vulicevic, Z. R., & Ferrari, M. (2008). Self-adhesive resin cements: a literature review. Journal of Adhesive Dentistry, 10(4).

- David-Perez, M., Ramirez-Suarez, J. P., Latorre-Correa, F., & Agudelo-Suarez, A. A. (2022). Degree of conversion of resin-cements (light-cured/dual-cured) under different thicknesses of vitreous ceramics: Systematic review. Journal of Prosthodontic Research, 66(3), 385-394.

Disclaimer: the views expressed in this article are those of the authors or product manufacturers and do not reflect the official views or policy of the US Department of the Air Force, the US Department of Defense, or the US Government. No federal endorsement of a manufacturer is intended.

SPEAR campus

Hands-On Learning in Spear Workshops

With enhanced safety and sterilization measures in place, the Spear Campus is now reopened for hands-on clinical CE workshops. As you consider a trip to Scottsdale, please visit our campus page for more details, including information on instructors, CE curricula and dates that will work for your schedule.

By: Melissa Seibert

Date: November 7, 2023

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts