Finishing Anterior Composite: How to Recreate Natural Enamel Morphology and Texture

Finishing and polishing create the shape and texture essential to restoring three-dimensional features of natural teeth. Mechanical finishing can be defined as all the procedures associated with contouring, eliminating marginal excess, and polishing restorations.

The Oxygen Inhibited Layer

Oxygen adversely affects the polymerization of any resin surface because the monomers within the composite resin react by free radical-induced polymerization. Oxygen is a well-known free radical scavenger; therefore, the initiators of composite resin polymerization bind to the oxygen rather than the monomer.

This only occurs at the surface of the restoration. For light-cured composites, the net result is a c.30-micron thick, sticky layer of unreacted monomer and oligomer on the surface of the restoration (the thickness for self-cured resin being somewhat more).

The presence of an oxygen-inhibited layer can result in several issues:

- It is prone to water absorption resulting in shade shifts and changes in translucency.

- The layer rapidly degrades in oral fluids affecting the surface polish and marginal adaptation.

- The sticky layer contaminates polishing discs and rubber points and affects the speed and quality of polishing procedures.

Fortunately, the solution is simple. Coat the entire surface of the restoration with glycerin and light curing for 40-60 seconds per surface. Prior to finishing, the glycerin is removed with an air water spray.

Do not use oil-based materials, such as Vaseline, as they are hydrophobic and make it difficult to remove them from the chairside.

Gross Finishing

Gross finishing aims to establish an outline form and macro-geometry (or shape) for the restoration. The first phase establishes mesial and distal line angles, giving the tooth more form and making it less amorphous and Chiclet-like. The line angle is the transition from interproximal to the facial surface.

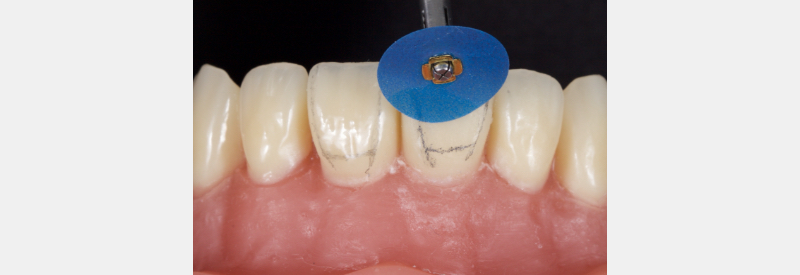

First, the desired line angles are marked in HB pencil on the restoration. The line angle is then established by using a coarse disc on the backhand motion moving horizontally from contact point to line angle.

The disc is then turned 90 degrees, and the mid-facial is defined with vertical disc motions while staying within the mesial and distal line angles.

This is classically achieved using a medium-sized 1/2 inch disc. In full-facial coverage cases, such as resin veneers, the disc is exchanged for a small-sized 3/8-inch disc, which is again used on the backhand from the gingival margin to the height of contour. This will establish the emergence profile and finish the margins.

This process is then repeated using medium-grit discs. If appropriate, mesial and distal mammelon groves are defined initially with either a carbide or fine diamond-grit flame burr at low speed with water spray. Movements should be horizontal rather than vertical.

This process is then refined using a rubber point, which can also be used to polish the gingival margin for resin veneers.

Polishing

The function of this stage is to eliminate porosities and scratches, in addition to improving marginal adaptation. This offers the following advantages:

- A high-quality, highly polished finish, which closely emulates natural enamel surfaces.

- Rough surfaces result in short-term staining and discoloration and esthetic compromise, in addition to plaque retention, which may cause secondary caries and periodontal issues.

The disc sequence from gross finishing is repeated with fine and superfine discs and a fine rubber point employed in the mesial and distal grooves to accentuate the mammelons further.

A further refinement may be the addition of perikymata, or incremental lines of pickerel. Although there are various ways of achieving this, the easiest and most effective method is to use a paper spiral mounted on a mandrel at low speed (3000-5000 RPM) without water and at high pressure in horizontal movements.

This final polish is achieved with 1-micron aluminum oxide, water-based polishing paste on a felt wheel. Running this vertically from gingival to incisal rather than mesio-distally is critical to avoid scratches in the final finish.

Initially, it should run at slow speed and high pressure, gradually reducing pressure and increasing speed as the polish penetrates the disc and the gloss appears on the restoration.

The final polished surface should closely emulate natural enamel.

References

- Beetzen, M. V., Li, J., And, I. N., & Sundström, F. (1996). Factors influencing shear strength of incrementally cured composite resins. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 54(5), 275-278.

- Barnes, C. E. (1945). Mechanism of Vinyl Polymerization. I. Role of Oxygen1. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 67(2), 217-220.

- Bergmann, P., Noack, M. J., & Roulet, J. F. (1991). Marginal adaptation with glass-ceramic inlays adhesively luted with glycerine gel. Quintessence International, 22(9), 739-44.

SPEAR STUDY CLUB

Join a Club and Unite with

Like-Minded Peers

In virtual meetings or in-person, Study Club encourages collaboration on exclusive, real-world cases supported by curriculum from the industry leader in dental CE. Find the club closest to you today!

By: Jason Smithson

Date: June 29, 2020

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts