FPDs vs. Implants, Part III: Length of Span and Vitality of Abutments

In this third article in my ongoing series about FPDs vs. Implants, I want to address two specific risk factors concerning FPDs: the length of the overall span (e.g., the number of pontics) and the risk of weakened abutments from endo and post-cores. As in the previous articles, I rely on well-done literature references to identify what we can expect in these clinical situations.

Whenever a discussion of length of span comes up in dentistry, it’s not uncommon to hear Ante’s Law brought up, which was published by Irwin H. Ante in a thesis in 1926. His thesis stated:

The total periodontal membrane area of the abutment teeth must equal or exceed that of the teeth to be replaced… The length of the periodontal membrane attachment of the abutment tooth should be at least one-half to two-thirds of that of its normal root attachment.

The net effect of Ante’s law was the utilization of multiple abutments to increase the periodontal membrane surface area of the abutments, something that significantly complicates the FPD and may lead (in some cases) to earlier failure.

Suffice it to say that multiple clinical studies have refuted Ante’s concepts, as was beautifully illustrated in the 2007 systematic review (Fig. 1).

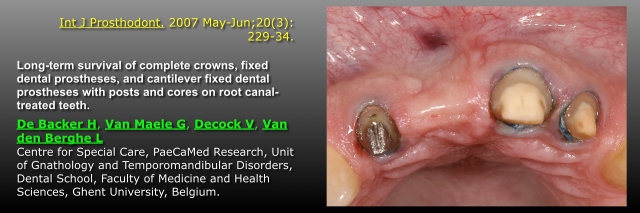

The article I will use to help us understand the risks of length of span and abutment teeth with posts and cores was published by a group in Belgium in 2007. The beauty of the article is that it looks at the following:

- The 20-year survival rates for single crowns on vital teeth or teeth with posts and cores

- Three-unit tooth-supported FPDs with vital abutments vs. one non-vital abutment with a post and core.

- Tooth-supported cantilever FPDs with vital abutments or non-vital abutments with post and cores

- Four or more unit tooth-supported FPDs with vital abutments, vs. with one non-vital abutment

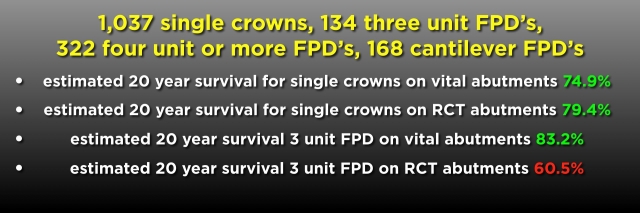

As in previous articles, I have color-coded the results. For single crowns at 20 years, whether the tooth was vital or had endo and a post and core, the success rates for either situation were not statistically different, at around 80%. For three-unit FPDs, however, the success rate at 20 years was dramatically affected by the presence of one abutment having endo and a post and core, dropping from 83% for vital abutments to 60% if one abutment was non-vital and had a post and core (Fig. 2).

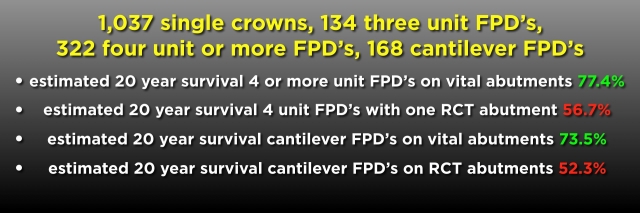

The impact is equally significant for four or more unit FPDs or cantilever FPDs. Dropping from 77% for four or more unit FPDs with vital abutments to 56% with one non-vital abutment with a post and core, and from 73% for cantilever FPDs with vital abutments to 52% if there was one non-vital abutment (Fig. 3).

This literature is significant to me in discussing implants vs FPDs to patients, as it provides evidence that allows us to inform them of the future risks of choosing an FPD if one of the abutments is non-vital and has a post and core.

The patient below exemplifies a patient in whom this literature was beneficial. He presented with an existing four-unit FPD from lateral incisor to lateral incisor, replacing the right central. In other words, the left central and lateral are used as double abutments.

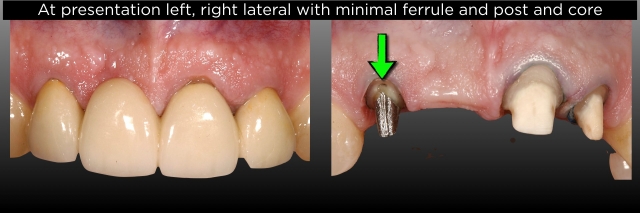

At his initial exam, there was chipped porcelain on the left lateral incisal edge, and the left lateral had come loose and could easily be pumped up and down. In addition, a radiograph revealed that the right lateral had endo and a large post and core.

This patient had been presented with an implant treatment plan by another dentist and refused it, knowing it would require bone and soft tissue grafting before implant placement (both an expensive and time-consuming course of treatment in his mind). He was adamant that he wanted a new FPD.

My personal belief is that my role is never to select or dictate a patient’s treatment plan, but instead to provide acceptable options and then present the pros and cons of each plan. For him, I presented a new FPD as one option, but I used the literature to show him how much risk there is in redoing an FPD that has already failed with a new one on the lateral with a post and core. In addition, I presented the implant option, which was far preferable. My proposal didn’t sway him.

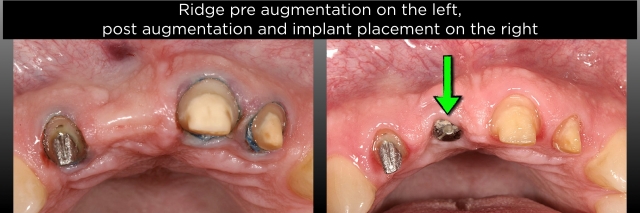

Realizing that, for either option, I needed to remove the existing FPD and make a provisional one, I convinced him to let me do that. I could then further assess the right lateral condition and find out if the left lateral was actually un-cemented or if the prep was fractured. He agreed to let me remove the FPD and place the provisional, assuming we would move forward with a new FPD. Below are photos of his existing FPD pre-treatment and what I found after removal. Note how minimal the ferrule is on the right lateral (Fig. 4).

I took the photos of the preps (Figs. 5–7) and walked him through what I saw, emphasizing again the high risk of doing another FPD as opposed to the implant. Ultimately, he agreed to see a surgeon for a consultation about what was involved and what the cost was for the implant, and in the end, chose to go through with the surgery and implant placement. This would have been a very high-risk case to redo the FPD.

Reference

- Lulic, M., Brägger, U., Lang, N. P., Zwahlen, M., & Salvi, G. E. (2007). Ante’s (1926) law revisited: a systematic review on survival rates and complications of fixed dental prostheses (FDPs) on severely reduced periodontal tissue support. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 18, 63-72.

SPEAR campus

Hands-On Learning in Spear Workshops

With enhanced safety and sterilization measures in place, the Spear Campus is now reopened for hands-on clinical CE workshops. As you consider a trip to Scottsdale, please visit our campus page for more details, including information on instructors, CE curricula and dates that will work for your schedule.

By: Frank Spear

Date: February 24, 2019

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts