Implant Maintenance for Long-Term Success

This article is written with the cooperation and permission of Dr. Tom Wilson.

Without a doubt, implants are the state-of-the-art in tooth replacement. With that comes the possibility of implant complications and even failure. Once the implant is completely integrated and restored, the key to long term success is in ongoing maintenance.

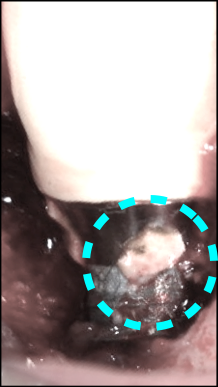

There are two major inflammatory processes that are associated with implants: peri-implant mucositis, or inflammation of the tissues around the implant, and peri-implantitis, or peri-implant mucositis with evidence of progressive bone loss.

It has been reported that in the five- to 10-year range, about 10 percent of implants and 20 percent of patients with implants will develop peri-implant infections. The simplest way to prevent them is careful placement, restoration and ongoing maintenance.

Hygienists have often been taught that they should not probe or scale around implants; if they do scale or probe, they should use specially designed plastic instruments. The implication is that calculus forms on a regular basis around implant platforms and subgingivally.

Biofilm and Implant Maintenance

While occasionally calculus forms, the more common enemies of long-term stability are the layer of biofilm that forms above the level of bone, cement retention and inappropriate occlusal forces.

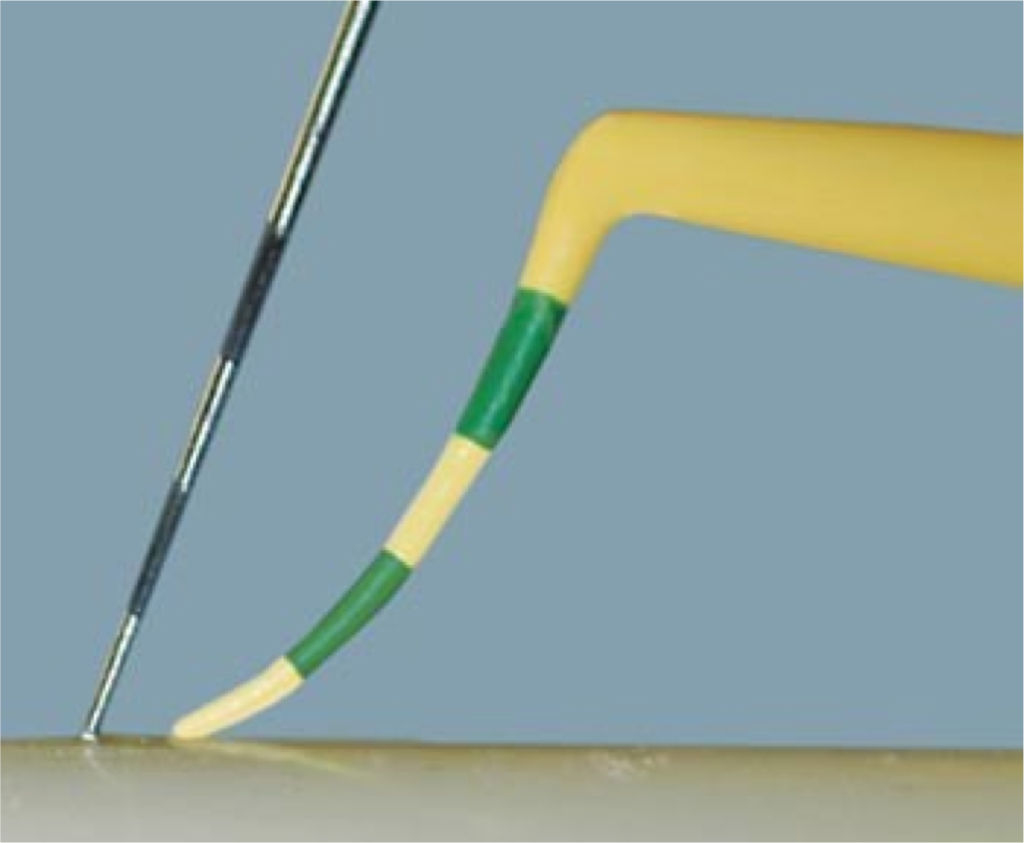

When considering routine maintenance, the hygienist should ALWAYS probe around implants. While a metal probe is highly unlikely to damage the implant surface, sometimes the use of a plastic probe makes it easier to probe around crown contours above the implant platform.

Bleeding upon probing is not normal; it is a sign of peri-implant mucositis and should be immediately addressed. The area should be thoroughly cleaned and polished, and the use of metal instruments is not contra-indicated if the scaling is not aggressive.

If the bleeding persists with good home care, proper restorative contours and thorough cleaning – even in the absence of bone loss – there is a chance that the implant is in early stages of peri-implantitis caused by retained cement or improper occlusal forces.

It takes three years for bone loss to become easily discoverable and often much longer. Cement does not always show up on radiographs, and if there is suspicion of retained cement or peri-implant bone loss, the case should be referred to a surgical specialist as soon as the issue is discovered. The faster it is treated the better the prognosis and if the cement is removed immediately, the disease either improved or completely resolved.

Implant Care and Scaling

Implant care, in addition to routine probing, should also include thorough removal of biofilm (plaque). In the rare instance of calculus formation around an implant, scaling is indicated. Some advocate plastic scalers, however, careful scaling with sharp metal instruments is more effective – and if done carefully will not harm the implant.

Patients should be instructed to floss around implants if possible and occlusion should be monitored and checked by the dentist annually at the very least. Reflective contacts, crossover interferences, working and balancing interferences that are destructive should be removed as soon as possible and centric contacts should not be heavier than adjacent teeth.

Preventing cement retention is more easily accomplished by utilizing custom abutments with margins at or less than 1 mm subgingival. Retraction cord can be placed around the abutment and should be placed in two sections, one on the buccal and one on the lingual. After the cement sets, the cord is lifted so it doesn’t pull through the proximals and avoids dragging cement with it. Cement should be lightly applied to the intaglio (interior surface) of the restoration, so minimal cement is extruded upon seating. Screw hole access should be filled with Teflon tape or a suitable alternative so only the top of the screw is covered, leaving a chimney open for cement to flow into instead of outside of the crown.

If these processes can’t be accomplished and the implant is at risk for cement retention, then a screw-retained restoration should be considered. Implants are predictably successful if appropriate protocols are followed.

Do you already use these processes? Do you do something completely different? Tell us in the comments below.

Steve Ratcliff, D.D.S., M.S., Spear Faculty and Contributing Author

VIRTUAL SEMINARS

The Campus CE Experience

– Online, Anywhere

Spear Virtual Seminars give you versatility to refine your clinical skills following the same lessons that you would at the Spear Campus in Scottsdale — but from anywhere, as a safe online alternative to large-attendance campus events. Ask an advisor how your practice can take advantage of this new CE option.

By: Steve Ratcliff

Date: October 15, 2015

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts